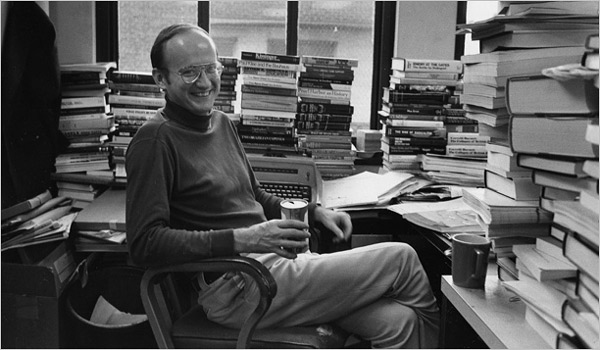

John Leonard in 1974, when he was the editor of The New York Times Book Review. (Jill Krementz)

John Leonard, 69, Cultural Critic, Dies

By MARGALIT FOX

New York Times – November 7, 2008

John Leonard, a widely influential and enduringly visible cultural critic known for the breadth of his knowledge, the depth of his inquiries and the lavish passion of his prose, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. He was 69 and lived in Manhattan.

His death, at Mount Sinai Hospital, was from complications of lung cancer, his stepdaughter, Jen Nessel, said.

Considered one of his profession’s most eminent practitioners, Mr. Leonard was at his death the television critic for New York magazine and a regular book critic for Harper’s Magazine. For many years he was a cultural critic for “CBS Sunday Morning.”

Mr. Leonard had a long association with The New York Times. In the 1970s he was the editor of The Times Book Review and was afterward a cultural critic at the paper. He contributed freelance reviews to The Times until last year.

A contributing editor of The Nation till his death, Mr. Leonard was also a past literary editor there, a post he held jointly with his wife, Sue Leonard, from 1995 to 1998.

His work was also found in The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic Monthly, The Village Voice and The Washington Post Book World, as well as on the National Public Radio program “Fresh Air.”

His portfolio took in books and television, the subjects for which he was best known, and film and politics, among other areas. Much of his work was infused, directly or obliquely, with autobiography, including forthright mentions of his struggle with alcoholism. In the late ’70s Mr. Leonard wrote a weekly column in The Times titled Private Lives, in which he chronicled doings in his Upper East Side home.

Mr. Leonard wrote a dozen books. These included several early novels and many volumes of criticism, among them “Smoke and Mirrors: Violence, Television and Other American Cultures” (New Press, 1997) and the profusely titled “When the Kissing Had to Stop: Cult Studs, Khmer Newts, Langley Spooks, Techno-Geeks, Video Drones, Author Gods, Serial Killers, Vampire Media, Alien Sperm-Suckers, Satanic Therapists, and Those of Us Who Hold a Left-Wing Grudge in the Post Toasties New World Hip-Hop” (New Press, 1999).

As a critic, Mr. Leonard was far less interested in saying yea or nay about a work of art than he was in scrutinizing the who, the what and the why of it. His writing opened a window onto the contemporary American scene, examining a book or film or television show as it was shaped by the cultural winds of the day.

Amid the thicket of book galleys he received each week, Mr. Leonard often spied glimmers that other critics had not yet noticed. He was known as an early champion of a string of writers who are now household names, among them Mary Gordon, Maxine Hong Kingston and the Nobel Prize winners Toni Morrison and Gabriel García Márquez.

Mr. Leonard’s prose was known not only for its erudition, but also for its sheer revelry in the sounds and sentences of English. Stylistic hallmarks included wit, wordplay, a carefully constructed acerbity and a syntax so unabashedly baroque that some readers found it overwhelming. The comma seemed to have been invented expressly for him.

In The Times Book Review in 2005, Mr. Leonard opened a review of an anthology of the writer James Agee with this single sweeping paragraph:

“Not every photograph ever snapped of James Agee caught him between pulls on a bottle or puffs on a cigarette. It only seems that way because the journalist/critic/novelist/screenwriter drank and smoked himself to death at 45, in 1955, at a time when postwar American culture conflated art with martyrdom and manhood with excess. Think of the poets lost to lithium, loony bins and suicide, the jazz musicians strung up and out on heroin, the abstract expressionists who slashed and burned themselves. Delmore Schwartz, Charlie Parker and Jackson Pollock pointed the way for Jack Kerouac, James Dean, Truman Capote, John Berryman, Elvis, Janis and Jimi. Like the Greek warrior Philoctetes, hadn’t they been allowed to play so brilliantly with their bows and arrows because they suffered suppurating wounds? So the iconic image, emblematic and self-destructive, was the Shadow Man — a Humphrey Bogart, a J. D. Salinger, an Edward R. Murrow, maybe even an Albert Camus. Agee, with his cold blue eyes, his thick dark hair and his handsome hillbilly Huguenot hatchet face, belonged on this wall of tragic-hero masks, at least till he inflated like a frog, from drinking alone in a Hollywood bungalow, and got kicked out of the 20th Century Fox studio commissary because he smelled so bad from never taking a bath.”

Mr. Leonard did not hesitate to be caustic when he felt it was required. He did not spare himself. Writing in The Nation, he reviewed “Private Lives in the Imperial City” (Knopf, 1979), a collection of his columns from The Times:

“It was hard enough for some of us to work up much interest in his cats and his stoop and his coffee grinder and his fondue pot and his qualms on the first go-round,” Mr. Leonard wrote, adding, “a book-length rerun is an exacerbation.”

John Dillon Leonard was born on Feb. 25, 1939, in Washington and reared there and in Jackson Heights, Queens, and Long Beach, Calif. He attended Harvard from 1956 to 1958 before dropping out to go to work; he later studied briefly at the University of California, Berkeley.

An ardent leftist all his life, Mr. Leonard worked early on as a teacher in Roxbury, a depressed Boston neighborhood; as an organizer of migrant workers in New Hampshire apple orchards; and as a community activist in Massachusetts during the “Vietnam Summer” of 1967. In an irony lost on no one, Mr. Leonard was ushered into journalism by William F. Buckley Jr., who in 1959 made him an editorial assistant on the National Review, a proud bastion of conservatism.

In September 1967, Mr. Leonard joined The Times as an editor in The Sunday Book Review. He became the paper’s daily book critic in 1969 and the head of The Book Review in December 1970. One of the signal events of his tenure there was a widely praised issue, published on March 28, 1971, devoted largely to books about the Vietnam War, many of them critical of United States policy. In 1975 Mr. Leonard became a cultural critic at The Times. He left the paper in 1982.

Mr. Leonard’s first marriage, to Christiana Morison, ended in divorce. Besides his stepdaughter, Ms. Nessel, he is survived by his second wife, Sue; two children from his first marriage, Andrew and Amy; his mother, Ruth Smith; and three grandchildren.

In 2006 Mr. Leonard received the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Book Critics Circle. In his acceptance speech, he thanked the writers who had occupied his time, day in and day out, for decades.

“My whole life I have been waving the names of writers, as if we needed rescue,” Mr. Leonard said. “From these writers, for almost 50 years, I have received narrative, witness, companionship, sanctuary, shock and steely strangeness; good advice, bad news, deep chords, hurtful discrepancy and amazing grace. At an average of five books a week, not counting all those sighed at and nibbled on before they go to the Strand, I will read 13,000. Then I’m dead. Thirteen thousand in a lifetime.”

John Leonard, Critic, Dies at 69

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Published: November 6, 2008

NEW YORK (AP) — Literary and cultural critic John Leonard, an early champion of Toni Morrison, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and many other authors, and so consumed and informed by books that Kurt Vonnegut once praised him as ”the smartest man who ever lived,” has died at age 69, his stepdaughter said Thursday.

Leonard died at Mount Sinai Hospital Wednesday night from complications from lung cancer, stepdaughter Jen Nessel said.

A former union activist and community organizer, Leonard was an emphatic liberal whose career began in the 1960s at the conservative National Review and continued at countless other publications, including The New York Times, The New Republic, The Nation and The Atlantic Monthly. He was also a TV critic for New York magazine, a columnist for Newsday and a commentator for ”CBS Sunday Morning.”

Leonard had the critic’s most fortunate knack of being ahead of his time. He was the first major reviewer to assess Morrison’s fiction and the first major American critic to write about Marquez. As the literary director for radio station KPFA in Berkeley, Calif., Leonard featured the commentary of Pauline Kael, before she became famous as a film critic for The New Yorker. Leonard was also an early advocate of Mary Gordon, Maxine Hong Kingston and other women writers.

”He really put a lot of us on the map,” said Gordon, who eventually became friends with Leonard. ”He was generous, warm, funny, and he didn’t make the mistakes that other men make with women writers. There was no discomfort or condescension with him, no feeling that he was the great man from on high. He was like a very tender big brother.”

His good work was appreciated. When Morrison traveled to Stockholm in 1993 to collect her Nobel Prize, she brought Leonard along, ”one of the most incredible experiences of his life,” Leonard’s stepdaughter said. Studs Terkel, who died Oct. 31, once called him ”a literary critic in the noblest sense of the word, where you didn’t determine whether a book was `good or bad’ but wrote with a point of view of how you should read the book.”

Said Leonard’s good friend, Kurt Vonnegut: ”When I start to read John Leonard, it is as though I, while simply looking for the men’s room, blundered into a lecture by the smartest man who ever lived.”

Leonard treated his subjects like lovers — to be protected, assailed, embraced. Literature was sweet madness. In 2007, accepting an honorary prize from his peers at the National Book Critics Circle, Leonard observed that ”for almost 50 years, I have received narrative, witness, companionship, sanctuary, shock, and steely strangeness; good advice, bad news, deep chords, hurtful discrepancy, and amazing grace.

…

Leonard’s own books included ”Black Conceit,” ”This Pen for Hire” and ”Lonesome Rangers: Homeless Minds, Promised Lands, Fugitive Cultures.”

Raised by a single mother, Leonard was born in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Washington, New York City and Long Beach, Calif. He dropped out of Harvard University, moved to New York and was taken on by William F. Buckley at the National Review after Buckley spotted a magazine article written by Leonard that scorned Greenwich Village.

”At one point, his job was monitoring the left-wing press,” Leonard’s stepdaughter said with a laugh.

Garry Wills, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ”Lincoln at Gettysburg” and also a former National Review writer, remembered Leonard as a ”terrific stylist” and an obvious talent at the magazine, where Buckley prized quality as much as politics.

”He was extraordinarily knowledgeable about literature. He always knew everything,” Wills said Thursday, adding that he regretted Leonard stopped writing fiction after such early novels as ”Wyke Regis” and ”The Naked Martini.”

”I thought he had a lot of promise, but John thought he was better off writing criticism.”

Although gravely ill near the end, Leonard did make sure to vote Tuesday, for Barack Obama, needing a chair as he waited at his polling place on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

”That was very important to him,” Nessel said.

Leonard is survived by his second wife, Sue Leonard; two children; one stepchild; and three grandchildren. A public memorial is planned for February.