It’s the birthday of poet Kenneth Patchen, born in Niles, Ohio (1911). He came from a working-class family — coal mining on his mother’s side, farming on his father’s, and while he was growing up his father was a steel worker in Youngstown. His Scottish grandfather loved to read aloud Robert Burns poems. And Patchen said that in Burns’ poems and his grandpa’s stories, “there was what you would call magic.” He started keeping a diary when he was 12 years old, wrote poems throughout high school, went to a handful of colleges, and traveled around the country working as a migrant laborer.

Then he went to a friend’s Christmas party and met Miriam Oikemus, a college student at Smith and an anti-war activist. The daughter of Finnish socialist immigrants, she had joined the Communist Party at the age of seven. Kenneth and Miriam fell in love and exchanged letters for a while — Patchen wrote her love poems. They got married in 1934. A few years later, when Patchen was just 26 years old, he suffered a terrible spinal injury while he was helping a friend separate two collided cars. He spent the rest of his life in severe pain, and went through three surgeries. The first two surgeries were helpful, and increased his mobility, so he was able to tour the country and give poetry readings. He partnered with Charles Mingus and the Chamber Jazz Sextet, and he set his poetry to jazz music, for performances and recordings.

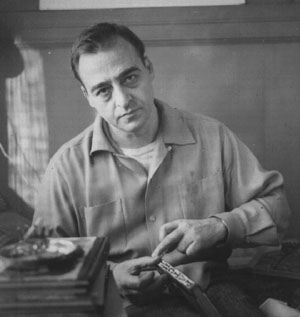

But during the last surgery, something went wrong and Patchen fell off the operating table and permanently ruined his back. He was bedridden for the rest of his life, but he continued to write and paint in bed. He said: “It happens that very often my writing with pen is interrupted by my writing with brush, but I think of both as writing. In other words, I don’t consider myself a painter. I think of myself as someone who has used the medium of painting in an attempt to extend.”

During his career, Patchen wrote more than 40 books of poetry and prose, much of it illustrated, including The Journal of Albion Moonlight (1941), The Memoirs of a Shy Pornographer (1945), The Love Poems of Kenneth Patchen (1960), and But Even So: Picture Poems (1968). He dedicated every book to Miriam.

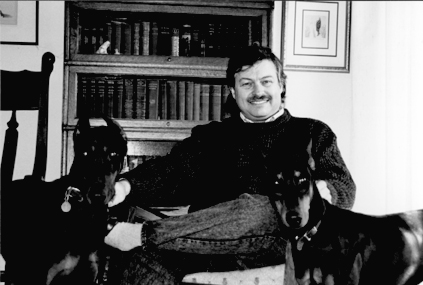

In 1945, two journalists published an article called “The Most Mysterious People in the Village,” about the life of Kenneth and Miriam Patchen. Miriam told the journalists that her husband was “absolutely impossible until he’s had a whole pot of coffee in the morning.” They wrote about visiting Kenneth Patchen’s bedroom: “The bed was massive and so was the man. He wore a faded gray sweatshirt with washed-out blue cuffs and pocket. The shirt was tucked into the waistband of black woolen trousers that were frayed at the cuffs. Patchen wore blue, maroon and tan Argyle socks, but no shoes. His body seemed muscular and powerful; his face delicate and sensitive. His skin was white and his eyes were a deep blue-gray.”

Years later, Miriam described their daily routine: “I’d be up earliest, go for the paper, read it. He’d awaken later, having finally gotten to sleep, have breakfast and look at the news, then get to work. ‘Get to work’ meant writing in bed, lying down. The upright sitting position was painful for him, then. I’d read, wash clothes, house clean, take coffee to him frequently. When we had almost no money life was the same as when we had a little. At 12th Street we always had the rent and money for utilities. With an advance from Mr. Padell we bought a couple windsor-style chairs, one easy chair and a table. What elegance those pieces gave to the doll house.”

Kenneth Patchen died in 1972, at the age of 60. Miriam Patchen remained a champion of leftist causes as well as her late husband’s poetry, and collaborated on his biography Kenneth Patchen: Rebel Poet in America (2000), by Larry R. Smith. Miriam Patchen died in 2000 at the age of 85, sitting up in a chair, reading.

Kenneth Patchen said, “It’s always because we love that we are rebellious; it takes a great deal of love to give a damn one way or another what happens from now on: I still do.”