Originally published in Arthur No. 17 (July 2005)

Be Your Own Guru

by Douglas Rushkoff

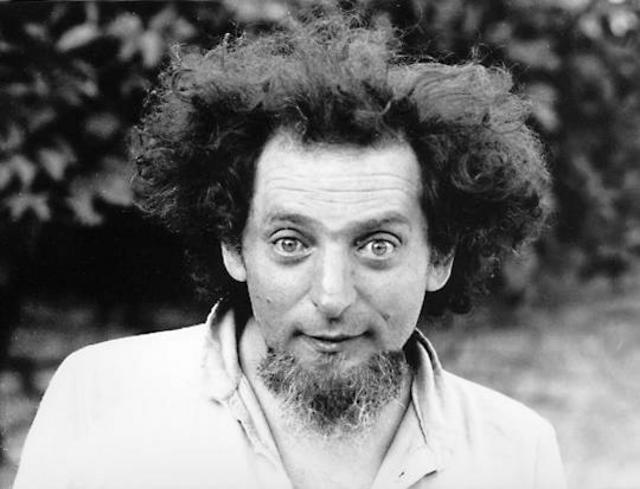

My good friend Jody Radzik—the guy who first introduced me to raves, actually—started up a blog this year. Jody is about the most loving and optimistic person I’ve ever known. That’s why I was surprised that instead of touting a new spiritual or cultural phenomenon, Radzik had decided to bash one.

Guruphiliac.com is dedicated to exposing the profoundly manipulative legions of grifters preying on the spiritually hopeful, as well as those teachers who simply go around letting people think they’re God, one guru at a time. It’s is an entertaining website, to be sure (for those of us who enjoy watching false messiahs unmasked) but it’s also important ongoing work. And the more I think about it, the more guru-bashing is starting to look like a form of optimism, in itself.

We all have gurus of some sort, whether we realize it or not. Even just for brief moments during the day. Haven’t you felt yourself regress to a childlike state, say, when talking to the auto mechanic about your car, the doctor about your test results, or your bartender about which Scotch to drink? In those moments—for an instant—the person becomes something of trusted authority in whose hands you trustingly place yourself. He will take care of me; he has my best interests at heart.

And in most cases, there’s of no great negative consequence to relinquish that authority. It’s just a drink, after all. And while we may want to self-educate a bit before undergoing surgery, we don’t need to learn how to remove an appendix in order to have one taken out. Unless we’re chronically ill, the doctor doesn’t remain our guru.

Even in situations where we’re learning to do something—say, hang-gliding or building a campfire—it can be helpful to surrender authority to the teacher. Certainly in their area of expertise, and for the duration of the lesson, the teacher is the master.

Where it gets tricky is when we assume that our protector’s expertise in one area makes him or her, somehow, better than us in all in all things. The Outward Bound leader knows how to build a fire and eat nettles—so in the context of the wilderness, he’s certainly got a leg up on you. But does this mean the little life lessons and platitudes he drops on you during difficult moments on the trail are universally valid teachings? They sure seem so in the moment, and they may occasionally be applicable to some other situation. But they’re just the musings of some guy.

Yes, it’s terrific to be able to surrender to the unassailable mastery of your cello teacher. She has stories to tell, techniques to share, and a holistic understanding of her instrument and music that you’d be well to emulate. And focusing on her brilliance, holding her phrases in your head like a mantra while you’re running your scales can make those interminable hours of practice more bearable and even productive.

But nowhere does there exist a genuine Bagger Vance or Horse Whisperer. There are no shrinks like Judd Nelson in Ordinary People or Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting. Sure, there are great golf pros, horse trainers, and therapists. But they’re just people. The successful therapeutic ending is not surrendering to the loving embrace of a psychologist, however much we may feel the need for a parental substitute or emotional surrender. In the trade, they call this transference, and at best it’s a means, not an ends.

It’s also a terrific technique for engendering loyalty. Back in the ’90s, I did some studies on coercive tactics. From the CIA Interrogation Manual to one of Toyota’s sales handbooks, I found the same basic strategy: confuse or disorient the subject until they regress to a childlike state, then step in as a parent figure and offer relief by accepting a confession or sale.

The guru operates the same way. At the end of the post-modern era, those brave souls courageous enough to see through the religions they may have grown up with emerge frightened and confused. An ex-orthodox Jew or a “recovering” Catholic is also a disoriented, vulnerable person. Although the latest cool bumper sticker says “Eastern religions suck, too,” it’s hard to go through the world suddenly without a ready system and someone to administer it. So, like people who end up in the same bad relationship time after time only with partners with different color hair, people who liberate too quickly or angrily from one system often end up adopting the next one that comes along.

The path of devotion offered by gurus is also a natural fit for those of us who are fed up with the relativistic haze of a world where there are no discernible rules, yet equally disillusioned by institutional religions that appear to have sold out to American consumerism. The guru offers absolutism. Certainty. A point of focus.

As one slick guru, chronicled on Guruphiliac explains on his website: “When you meet a master, you have two choices. Transform or walk away. You cannot be in his presence and remain the same.” Uh, yeah. In other words, conform to his reality or scram.

The guru is the starting place from which all other decisions are to be made. You start with the guru as the one perfect point in the universe, and from there everything else can fall into place. If the guru has instructed you to eat a certain food or do a certain practice, then—according to the logic of gurudom—everything else you have to do for this to happen is part of the perfection. Slowly but surely, surrender to the guru requires you to reject pretty much everything that doesn’t fit whatever model of the world he’s offering you.

But, honestly, that’s what the devotee was after in the first place. An excuse to do or not do all that other confusing stuff in life like encounter people with different ideas, wrestle with the questions of existence, and accept that nobody really knows what happens when we die.

Most of us who have had gurus eventually see something awful—like sexual exploitation, financial abuse, or faked magic—that turns us off. (If we see the guru as perfect, then those blowjobs and false claims get justified: perhaps the guru is testing us, or breaking our hang-ups, At least for a while.) Or we decide that this guy is just too much of an asshole to really be enlightened. Or we simply tire of the idea that “enlightenment” is around the corner, and decide that life is just fine without enlightenment. And getting to that point is a beautiful thing in itself. If an experience with a guru really teaches one the futility of aspirational spiritual quests, then it can even be worth the time, money, and humiliation.

The biggest spiritual victim in the equation is the guru, himself. He’s just a person, after all, who probably had a profound spiritual or psychedelic experience and began to speak or write about it romantically. Charismatically. And this invites admirers and would-be devotees. The guru-in-waiting may not even mean to attract this sort of attention – at least not at the beginning. It’s just the kind of positive reinforcement that naturally comes to a person who speaks passionately about something. I’ve felt shades of it myself, especially when I’m doing a book tour or a lecture about a transcendental topic. Wide-eyed audiences, especially those in areas where don’t get many weird authors, gobble up every word. College students want to hang out late into the night, talking over drinks (or better) about alternate realities, magick sigils or the nature of time. How hard it is not to speak about magick in a magickal way?

And it feels good to give people answers—something to chew on for a while, even if, like a Zen koan, it eventually turns out to be little more than a puzzle to keep them occupied and less afraid of death or existence for a while. To accept this path of the guru, though, however tempting, is certain doom for the artist, writer, or philosopher. It turns his existence from a question into an answer, from flux to certainty—from a life into a death.

Most of the generation of weird sages above my peers and me has died. So now we’re the ones invited to run workshops at places like Esalen and Omega, to speak to groups of young spiritual people or counterculturalists, and to share our insights on the occult, psychic realms, and religious practices.

Lucky for me, I’ve been on the receiving end of the guru dynamic, so I know how and why to avoid doing it, myself. Avoidance usually entails deconstructing an event before it begins, decrying the self-help bias of America’s spiritual community, and then teaching in the most straightforward manner possible, even at the expense of mystery. (I’m married with a daughter, now, so the temptation to succumb to the consequence-free fringe benefits of retreat weekends has diminished, anyway.)

But as I look around me, I see other members of my generation claiming to see the weirdest things, to be enlightened, or to be able to offer access to energies from alternate realms. And it makes me sad and just a bit angry. The insights, such as they are, get lost in fiction. Even if a few of us do happen to be carrying some fragment of real wisdom, the object of the game is to get out the way so the wisdom can be shared. I mean, if I really thought I was channeling something or someone, I’d do it over the radio, anonymously.

The answer, of course, is for all of us to get over our need for gurus. Remove the demand and the supply should dwindle, too. I mean, most of us have already endured one set of parents. Why go through that again? The stuff they didn’t do right simply cannot be corrected. Mourn what you missed and move on. (Meanwhile, if it’s magic you’re after, go to Vegas and see a show. No one can teach you how to walk on water or be in two places at once. And if you do get awakened someday, whatever that means, you’ll realize this very need to talk to God or see the light is what’s been getting in the way of your clarity the whole time. Besides, is it really magical abilities and transcendent experiences you’re after, or merely escape from the pain of everyday experience?)

The truth about the great spiritual quest of our species is that it just can’t work with followers and leaders. There’s way too much duality built-in to such a scheme. Hierarchies are fun, but they’re a construction. I’ve been around the spiritual block more times than I care to mention, and have read the work of the very best teachers and philosophers I can get a hold of. And as I’ve come to see it, there is no such thing as awakening. It’s a ruse. Think about it: the whole concept of reaching enlightenment is so steeped in dualism, expectation, and obsession with self. The word “enlightenment” may sell books and earn devotees, but it doesn’t refer to anything real. It doesn’t exist. The true spiritual path may just be a matter getting over that fact, and in the process, learning to express and enact as much compassion as you can. That’s why I see guruphiliac.com as an optimistic effort; it assumes we’re ready to let all this go.

If you’ve got to start with some perfect point in the universe, start with yourself. There’s no path to take, no one else to follow. And you don’t need anyone to tell you this for it to be true. All the places you might get to are equally valid, because everyone is just as lost as you are. The sooner we all admit this, the sooner we can begin to orient to one another as siblings and partners in the great adventure.