Originally published in Arthur No. 7 (Nov. 2003)

REVIEWS BY C and D

The Hidden Hand

Divine Propaganda

(Meteor City)

C: This is Wino’s new band…

D: From St. Vitus! And the mighty Spirit Caravan!

C: This is prime Wino. Very focused. Full-on Sabbath power trio. Political eco-stoner stuff. “I feel the sky cracking/I feel the ice melting/I feel the world dying.”

D: Track 8 is an unstoppable beast!

C: “The Hidden Hand [theme].” Yeah, this is solid shit. Kinda conspiracy-minded. I mean, just look at the name of the band—

D: As we said in the days of old, these guys can carpet a good chair!

C: He put a suggested reading list in the CD tray, you don‘t see that too often with metalish bands. Edmund O. Wilson, The Future of Life… Greg Palast, The Best Democracy Money Can Buy… Wait a sec. David Icke?!?

D: Who is this guy?

C: That’s the British dude who sez that the world’s political and economic leaders are not humans, they’re actually reptiles from outer space working in a conspiracy together. Very V. I think he’s saying that 9/11 and its consequences were predicted in the pages of Alice in Wonderland. Obviously he’s onto something.

D: ?

C: I’m joking. But I wonder if Wino is in on the Icke joke. Seems like he’s taking it seriously…?

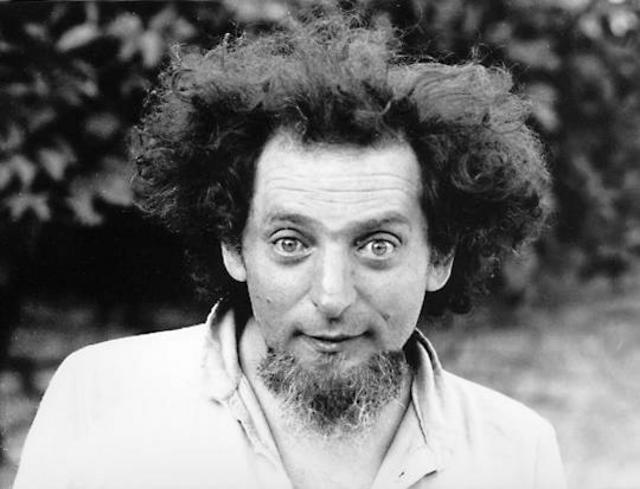

D: Wino is the best. But he looks totally different with a beard. I don’t know if I approve.

The Raveonettes

Chain Gang of Love

(Columbia)

D: Is this the new Jesus and Mary Chain album?

C: No, it’s this Swedish band called the Raveonettes.

D: Why don’t they just call themselves the Raveisionists?

C: Who do you think you would win in a rumble between these guys and the Black Rebel Motorcycle Club?

D: Agh! I hate those Black Rebel guys! So boring live.

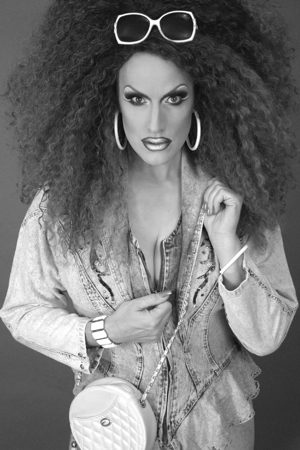

C: Their second album is terrible. I think it could be the end of the road for them. But who cares. The Raveonettes have a six-foot chick singer, I think she could take them out.

D: Swedish precision! There’s a Spector back beat jangle here.

C: Melodies and distortion, it always sounds good. You gotta cop to it, there’s some good stuff on here.

D: Yes, this song [“That Great Love Sound”] is good. But it’s nothing that will make you spill your ice cream on the floor.

C: …?

Ween

Quebec

(Sanctuary)

D: Incredible. Who is this?

C: Ween.

D: Each song? No, it can’t be. They are all so different

C: Yes. That’s what they do! I’ve been trying to get you to listen to them for years—

D: Every song is a population of musical influences of the last 20 years. It all sounds familiar but beautifully deranged. You don’t know where the sound comes from, it’s written down in the backpages of your brain and heart but you can’t locate it.

C: This song “Zoloft” is fantastic.

D: Zoloft—that’s some good stuff there. The doctor’s medicine is working. I’m seeing different colors in a different way. Yellow even is starting to look good.

C: Listen to this one [“Transdermal Celebration”]: it’s like an Oasis song except it’s really good.

D: None of those Anglo-Saxons can rock like Americans! [Listening to “So Many People In the Nieghborhood”] These guys are like the Residents, some of this stuff. But it’s also very melancholic. This song [“Among His Tribe”] cuts straight to the bone.

C: This one “Captain” is my favorite. Very Pink Floyd. Listen to those drums. He’s stuck on a spaceship and they WON’T GO BACK!

D: “Tried and True”—this is middle American melancholy. Another weightless psychedelic Byrds song. Record store clerks rejoice. They’re the best. They’re too good for me. It’s like Ian Curtis said, I looked behind the doors of time, there was nothing there to see.

C: ???

D: [still listening to “Tried and True”] …Is that a sitar?!? No.

C: Yes it is.

D: It cannot be.

C: They’re putting the India in Indiana.

D: Ween are a jukebox. One way not to disappear up your own ass is to disappear up others’.

C: Right… I guess that’s one way of looking at it.

Terry Hall & Mushtaq

The Hour of Two Lights

(Astralwerks)

C: This should be the soundtrack for that hookah place on Sunset’s sound system.

D: Yes! Exactly!

C: It’s the Specials guy. They sound like melancholy gypsies.

D: Dignified, beautiful.

C: Class, yeah? Two cultures, maybe three.

D: I like it! Let me look at the box.

C: It’s like a new kind of traditional music.

D: Yes… [thoughtful] Can we order some Indian food now?

Brant Bjork

Keep Your Cool

(Duna Records)

C: Brant Bjork from Kyuss and Fu Manchu and Mondo Generator’s new record.

D: Is that him singing?

C: [Nods ‘Yes.’] He’s playing all of the instruments too.

D: [Thumbs up.] Vintage ‘70s rock! And Thin Lizzy too! Wow. The reggae bass on “Searchin’”… scary. Reminds me of David Bowie. Or Blondie.

C: This is kinda Foghat, yeah? Plus the Cars… Here he is in falsetto… “Sister’s got the inside infoooooh!” He should do that more. Michael Jackson, almost. Very cool. This is really good, such a good feel, laidback. Compare this to that new Nebula album, ech. This is the good shit here.

D: I always liked him, Brant Bjork! Thanks for the Red Sun, Mr. Bjork.

C: Check this out: dude is putting the album out only on 12-inch vinyl. No CDs!

PFFR

United We Doth

(Birdman)

C: Bad Ween.

D: Sick.

C: I dunno, dude.

D: I love it. How did they get Snoop Dogg for this?

C: I think one of the PFFR guys is a South Park guy or something, that’s the word on the street. I don’t what street that is, but whatever, there you go. This sound like bad acid trip music. Very bad acid trip.

D: I love it.

The Rapture

Echoes

(Universal)

D: I know this. This is the Moving Units.

C: No, this is the Rapture.

D: They do the same thing.

C: Yeah, well… The Rapture have been going for a while longer, but yep it’s the same influences… Gotta say this is kinda disappointing. That one single on here from two years ago [“House of Jealous Lovers”] is cool but after a while…

D: It’s good but COMPLETELY unoriginal. Birthday Party. Pop Group. Gang of Four. They love that music.

Erase Errata

At Crystal Palace

(Troubleman Unlimited)

D: Same thing! I’m already sick of this. All of these people love the Pop Group. They love this music to DEATH.

C: It does seem pretty little limited on record. But you gotta admit it’s well done. This reminds me a whole lot of that amazing band Lilliput, you remember them? From Switzerland. Some of this stuff seems almost directly ripped. Well maybe they’ll get more interesting on the next record…

D: Lilliput, call your Swiss lawyers!!!

Pretty Girls Make Graves

The New Romance

(Matador)

D: (sighs) More of this stuff? Everybody likes the Pop Group. They like them too much.

C: I dunno, I think this is pretty good. I’d be curious to hear the next record, to see where they go.

D: Whatever. Can we listen to the new Kraftwerk again?

High Llamas

Beet, Maize & Corn

(Drag City)

C: [singing] “Orange crate art/is where it starts.” Oh wait, wrong album. This is pretty shameless Brian Wilson/Van Dyke Parks, sheesh.

D: Take it off the CD player now.

C: All arrangement, no hooks… Beach Boys without harmonies or melodies–what’s the point? Nice wallpaper stuff, though. I think he could do good soundtrack music. Maybe with Alison Anders, this is her type of shit.

D: This guy should move to Nashville or go back in time to the Brill Building. ENOUGH! Turn it off NOW or I’m leaving.

Festival in the Desert

(World Village/Triban Union/Harmonia Mundi)

C: This is my favorite album out of the whole bunch.

D: This is Malian stuff, right?

C: Yes. This whole CD was recorded live at this festival in the desert, as you might’ve gathered from the title. Pretty amazing stuff.

D: [Listening to “Buri Baalal” by Afel Bocoum] So beautiful. Listen to how the women sing!

C: Yeah, see? This music has everything: melodies, chants…incredible rhythms… all those stringed instruments, I don’t even know what they are. Guitars, I guess.

D: Beautiful.

C: They’re doing a DVD of this, that should be amazing. Sand and candles and this music: what a setting. Tinariwen are on here, they’re amazing.

D: Those are the guys who sound like Junior Kimbrough right?

C: Exactly—the electric guitars are just like his, but I bet they never heard each other’s music. Makes you wonder how far back Junior’s music really goes… Ali Farke Toure’s on here too. And this Native American rock group Blackfire, they have this old guy singing all through it. The Robert Plant song is great.

D: [Listening to Tartit’s “Tihar Bayatin”] So hypnotic… This is the deep stuff, man. The deepest stuff. I’m serious.

House of Low Culture

Edward’s Lament

(Neurot)

D: Dark night music.

C: Yeah, this is really good stuff. Desolate. Subtitled “An Account of Salvation and Redemption in 9 Movements.” So there you go.

D: No moon!

C: Just an electric hum.

D: And vampires!

C: It is pretty spooky. This first track reminds me a lot of Thomas Koner, in a bat sanctuary. The second reminds me of Begotten…

D: So good, so good.

C: This third, with the guitar? Very Gira. Also reminds me of that one vampire film, actually. The Addiction? The Abel Ferrara one. This whole album is soooo evocative. Dark, trippy, but not silly—there’s no stupid trance beats.

D: You better get the candles ready!

C: File next to Coil. I’m definitely gonna be spending some late winter nights listening to this…

D: Do you know that artist Ernst Ffolks? His sense of apocalypse I identified with totally. I have incredible books at my house.