“Riding Out the Credit Crisis” by Douglas Rushkoff

from Arthur Magazine No. 29/May 2008

There’s two kinds of people asking me about the economy lately: people with money wanting to know how to keep it “safe,” and people without money, wanting to know how to keep safe, themselves.

Maybe it’s the difference between those two concerns that best explains the underlying nature of today’s fiscal crisis.

Is what’s going on in the economy right now really worse than anything that’s happened in the past few decades? Are we heading towards a bank collapse like what happened in 1929? Or something even worse?

On a certain level, none of these questions really matter. Not as they’re being phrased, anyway. What we think of as “the economy” today isn’t real, it’s virtual. It’s a speculative marketplace that has very little to do with getting real things to the people who need them, and much more to do with providing ways for passive investors to grow their capital.

This economy of markets was created to give the rising merchant class in the late middle ages a way to invest their winnings. Instead of actually working, or even injecting capital into new enterprises, they learned to “make markets” in things that were scarce. Or, rather, in things that could be made scarce, like land.

That’s how speculation was born. Speculation in land, gold, coal, food…pretty much anything. Because the wealthy had such so much excess capital to invest, they made markets in stuff that the rest of us actually used. The problem is that when coal or corn isn’t just fuel or food but also an asset class, the laws of supply and demand cease to be the principal forces determining their price. When there’s a lot of money and few places to invest it, anything considered a speculative asset becomes overpriced. And then real people can’t afford the stuff they need.

The speculative economy is related to the real economy, but more as a parasite than a positive force. It is detached from the real needs of people, and even detached from the real commerce that goes on between humans. It is a form of meta-commerce, like a Las Vegas casino betting on the outcome of a political election. Only the bets, in this case, change the real costs of the things being bet on.

That’s what happened in the housing market and the credit market—which, these days, are actually the same thing. Here’s the story, in the simplest terms:

Bush’s tax cuts and other measures favoring the rich led to the biggest redistribution of wealth from poor to rich in American history. The result was that the wealthy—the investment class—had more money to invest, or lend, than there were people and businesses looking to borrow.

The easiest way to bring more borrowers into the system—and to create more of a market for money—was to promote homeownership in America. This is precisely what the Bush administration did, touting home ownership as an American right. Of course, they weren’t talking about home ownership at all, but rather pushing people to borrow money tied to the value of a house. If people could be persuaded to take mortgages on homes, real estate values would go up for those already invested (like land trusts and real estate funds) and banks would have a market for the excess money they had accumulated.

In short, there was a surplus of credit in the system. Americans were encouraged to borrow in the form of mortgages, which created demand for the credit banks wanted to sell. In many cases the credit itself wasn’t even real, but leveraged off some other inflated commodity that the bank or investor may have owned.

Banks and mortgage companies invented some really shady and difficult-to-understand mortgage contracts, designed to get people to borrow more money than they could. Banks didn’t care so much about lending money to people who wouldn’t be able to pay it back, because that’s not how they were going to earn their money, anyway. They provided the money for mortgage companies to lend, and in return won the rights to underwrite the loans when they were packaged and sold to other people and institutions.

So a bank might provide the cash for a bunch of loans, but then get it back, plus a huge commission, when those loans were packaged and sold to someone else.

Lots of people take out mortgages, and housing prices rise. This is used as evidence to convince more people that real estate is a great investment, and more people buy into the housing bubble. Lots of these people put little or no money down, and buy mortgages whose interests rates are going to change for the worse. But they believe the price of their home is inevitably going to go up, and pin their futures on the idea that they can refinance their mortgage before their rate changes. Since the house will be worth more, the mortgage for what they owe should be easier to get; it will represent a smaller percentage of the new total cost of the house.

Of course, this was dumb. Banks didn’t really care (because they weren’t holding the bad paper) but the people investing in those “mortgage-backed securities” were slowly getting wise to the fact that many of the borrowers were in over their heads. What to do? The credit industry went ahead and lobbied Washington to change the bankruptcy laws. While corporations could claim bankruptcy and stop paying for their retirees’ health coverage, individuals would no longer be able to claim bankruptcy, and even if they did, they would still owe their creditors the money they borrowed, forever. The credit industry spent over $100 million lobbying lawmakers for the new provisions.

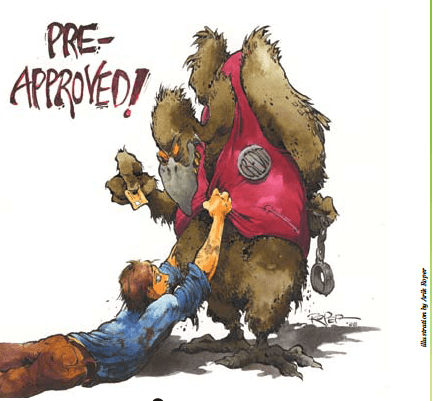

Then, just like the credit industry predicted, loans start going bad. (The industry labels these loans “sub prime” because they want to make it look like the borrowers were somehow less-than-respectable people. But the term really just refers to a less-than-respectable loan.) As homeowners default on their mortgages, housing prices start to go down. This, in turn, makes it impossible for people to refinance their mortgages when they thought they would; in fact, now many homeowners actually owe more on their home than the home is worth. How can you refinance a million-dollar loan on a house that is only worth half that? You can’t, so instead you have to hold onto the variable-rate loan that you foolishly bought from the predatory lender. The rate rises higher and faster than you can pay it.

Lenders go ahead and start foreclosing on properties, kicking out the mortgage holders who can’t pay. But this creates another problem: what to do with the house? It’s not even worth the outstanding portion of the loan, in many cases. And even if they can sell it, how to distribute the money? No one even really knows whose mortgages belong to whom, as they’ve been sold as parts of packages, again and again, to different lenders, pension funds, money markets…you name it.

This leads to what became known as the “credit crunch” or “liquidity crisis.” No one feels good about lending money anymore because so much of it was tied in one way or another to these bad mortgages. The creditors don’t want to take possession of all these foreclosed homes, and they turn to the government for help.

Under the guise of helping homeowners “stay in their homes,” the government starts bandying about various “relief packages.” The Treasury department and the Fed are actually taking a two-pronged strategy towards fixing the problem. One prong is cynical PR, and the other is just plain stupid.

First, they want to create the illusion that something is being done, so they talk about “superfunds” to bail out homeowners, freezes on rate hikes, checks mailed to every taxpayer, and other useless gestures. They do all this to appease angry consumers and consumer advocates because they won’t want real lending industry regulation (like what Barney Frank and other progressives are pushing for) to gain any traction.

Second, they want to make more money available to the creditors (banks), so they can keep lending money—because this is their business. So the Fed lowers interest rates again and again. Banks get more money, and guess what? We’re back where we started: with tons of money and nowhere to invest it! By lowering the “prime lending rate,” they simply add to the surplus cash that created the problem in the first place.

Of course, both measures serve to stave off panic selling, because it seems as though something real is being done. Homeowners may get a slight delay in the paralyzing rate increases on their mortgages, giving banks and creditors the chance to make a more orderly exit. They will bail from these mortgages while selling the artificially secured credit to the likes of you and me through money market accounts and other retail products. They just need time to make sure the real losses trickle down to someone else.

And remember: this whole mortgage fiasco is just a little preview of what happens next year when the credit card industry faces the very same self-imposed “crunch.” In the case of mortgage lenders, at least the terms of the loans were disclosed. Credit card companies—which are some of the very same banks that are in the mortgage mess today—are busy rewriting their policies, increasing rates, and adding fees to the policies of people already in debt to them.

You know those little ‘inserts’ in your credit card bill? Read them, and you’ll find out, like I did, that some credit card companies have begun charging interest on your purchases from the moment you make the purchase. You pay finance charges even if you pay your whole bill every month. Most people carry big balances, so they won’t notice the additional charges, or at least that’s what the credit card companies are—quite literally—banking on.

* * *

After a certain point, consumers just won’t be able to pay their bills. Even though they’ve paid the cost of their purchases several times over, they’re simply buried in interest and interest on the interest, sometimes compounding at a rate of 30 or 40 percent per year. The creditors know this, which is why they’ve sold a lot of this debt to other banks, pension plans, money market funds…you get the picture: the kinds of places where we invest our retirement money. The banks invested in us; we were the assets. Now that we’re about to go broke, they’re busy selling us to other financial institutions in a game of musical chairs that will cost the last debtholder a lot of money. Of course, unless we can convince some foreign sheiks to buy some lousy US assets with their oil money, that last debt holder will end up being you and me.

Over the past few months I’ve spoken to top strategists at some of the biggest banks in the world, and they share my perception of the scenario. Most of them are “holding cash” as their main investment strategy, spread out over a few of the major currencies. Those making money are doing so by short-selling shares of other companies in the same finance industry that they supposedly work for.

The bigger picture, of course, is that speculation just worked too well for too long. The disparity between the market values and real values (rich people and poor people) got too large. Every asset class, even money itself, got too expensive. We became more valuable for our borrowing power than our labor—which also meant there was no way to work off our debt. Meanwhile, the people using reality as an investment vehicle have overwhelmed the real economy on which their “structured investments” are based.

Sure, this has happened before. It’s just that, traditionally, when wealth disparity got too great and there wasn’t enough money in the right places, the wealthiest bankers temporarily suspended their greed to bail out the system. Or progressive tax policies opened corporate coffers, permitting a “New Deal” that employed people while rebuilding the infrastructure required to make real things and provide real services to citizens.

Today, however, such temporary restraints on greed are systematically untenable and philosophically unthinkable. Conservatives are still so angry about New Deal reforms of the 1930s that that they have infused politics and banking with an economic ideology that sees any regulation of worker exploitation or predatory investment as anti-capitalist, anti-American, and even anti-God.

So instead we are the beneficiaries of “wink” reform: stuff that’s supposed to make us feel good while reassuring the speculators that their interests will remain paramount. A few hundred dollars mailed to every American family creates the illusion that government is lending a helping hand, but this money is not redistributing anything. It’s being taken from the same people who are receiving it, in the hope that they’ll just pump it back into the system at Wal-Mart or the Exxon station.

Whether the coming economic crisis will be deep or shallow is left to be seen. We may be at the start of the kind of depression our grandparents lived through in the ’30s, or we may simply experience what our parents lived through back in the ’70s. Foreign investment trusts may come in and buy our biggest banks and turn us into global citizens through the very World Bank policies we were hoping would turn all of them into US vassals.

Whatever the case, the best thing you can do to protect yourself and your interests is to make friends. The more we are willing to do for each other on our own terms and for compensation that doesn’t necessarily involve the until-recently-almighty dollar, the less vulnerable we are to the movements of markets that, quite frankly, have nothing to do with us.

If you’re sourcing your garlic from your neighbor over the hill instead of the Big Ag conglomerate over the ocean, then shifts in the exchange rate won’t matter much. If you’re using a local currency to pay your mechanic to adjust your brakes, or your chiropractor to adjust your back, then a global liquidity crisis won’t affect your ability to pay for either. If you move to a place because you’re looking for smart people instead of a smart real estate investment, you’re less likely to be suckered by high costs of a “hot” city or neighborhood, and more likely to find the kinds of people willing to serve as a social network, if for no other reason than they’re less busy servicing their mortgages.

The more connected you are to the real world, and the more consciously you reject the lure of the speculative ladder, the less of a willing dupe you’ll be in the pyramid scheme that’s in the process of collapsing all around us at this moment.

Think small. Buy local. Make friends. Print money. Grow food. Teach children. Learn nutrition. And if you do have money to invest, put it into whatever lets you and your friends do those things.

Douglas Rushkoff writes books about media, technology, and values. He’s currently working on a project called “Corporatized,” which will explore how chartered corporations disconnected us from reality. rushkoff.com