Acceptance (doesn’t equal) Acquiescence

by Douglas Rushkoff

from Arthur No. 24 / Oct 02006:

I’ve been debating for a while about whether to do this. Whether to come right out and say it. On a certain level, it’s like shouting “fire” in a crowded theater. What good is it to announce a problem if I don’t have a ready solution at hand? Furthermore, what if sharing this information – this perspective on our predicament – simply exacerbates our paralysis to do anything about it. I mean, fascism breeds best in populations that have been stunned into complacency, cynicism, or despair.

(That’s called a “buried lede” – a publishing term for hiding the main idea of a story deep within a paragraph. Editors don’t like it because it makes it hard for the reader to figure out what an article is about. But I felt it necessary because, well, I’m not quite comfortable talking about it too directly, just yet. This fascism stuff.)

It all became blindingly clear to me the morning I found out Ken Lay was dead. I was listening to the radio – to a friend of mine, actually, reading the news report on NPR. He was explaining how the dishonored corporate elite criminal, the former CEO of Enron, had a fatal heart attack before he had the chance to spend the rest of his life in jail. Because of certain technicalities in the law, this also meant Lay’s family would in all likelihood be able to keep the millions of dollars that would have otherwise been paid back to Enron employees and shareholders in court fines.

The newsreader opined that Lay’s death might have been suicide, and not just for the money. Lay was in on those early secret energy industry meetings with Dick Cheney – the ones where they figured out oil prices and the Iraq War and other matters of state – and, facing prison, the fallen corporate superstar could have posed a security risk if he had leaked information about what had transpired to other prisoners or, worse, the FBI in trade for better living quarters.

But, given all that, I couldn’t bring myself to believe Lay was dead at all. If you’re that rich and powerful, why die? Why not just get a hold of some corpse, pay-off a coroner, move to an island and call it a day? This is no grassy knoll feat. It’s not even CSI, but early 90’s Law & Order. No big deal for a guy intimately connected with one of the most actively clandestine administrations in US history.

That same July morning, when news of North Korea’s failed nuclear test launches were broadcast, I didn’t feel sure I was being told what was happening, either. Not that news agencies can really know, either. Did they launch? Were they thwarted by a US counterstrike, or by their own ineptitude? Do they even know? Do we?

I’m not saying one thing or the other happened – just that I stare at the news and don’t believe anything they’re saying. I’ve got no idea. And it feels really weird.

I find I can trace this sense of uncertainty to the 2004 election. The 2000 election was crooked, but the fraud was rather out in the open. We watched hired thugs stop the Florida recount by trying to break into the room where the counting was happening – and thus delay the process long enough for the Supreme Court to choose Bush as the President. But the 2004 voter fraud in Ohio, fully documented by Robert Kennedy Jr., among others, was an entirely more hidden affair. Diebold voting machines, teams of fraud squads, and election officials too afraid that disclosure of what happened will turn people off voting forever.

Those of us who try to stay even remotely connected to what is going on in the world around us have enough hard evidence to conclude with certainty that voting in America has been systematically and effectively undermined by the party currently in power. In an increasing number of precincts, how people vote – if they are even allowed in – no longer has a direct influence on how their votes are tallied.

It’s sad and confusing not to live in a democracy, anymore. And while it’s quite plainly true, it’s a bit too unthinkable for most sane people to accept. It goes in the same mental basket as more outlandish (if not unthinkable) thoughts — such as dynamite on the WTC or no airplane crashing into the Pentagon — even though, in this case, it’s not conjecture, it’s just plain real.

So what I’m coming to grips with is accepting that I don’t live in a democratic nation, and that the propaganda state attempted in 1930’s Europe did finally reach fruition here in the U.S., just as Henry Ford and those of his ilk predicted.

Maybe I’m just old, and have a very idealistic view of democracy. When I was a kid, we were all told that this is a government of the people, and that our votes provided a check on the power of our leaders. That’s why we called them “elected.” Or maybe it’s just naïve to think that representative democracy could have worked the way it was presented to us.

The other side – the fascist side – does have an argument to make, and they’ve been making it since Woodrow Wilson was president. Having run on a “peace” campaign, Wilson later decided that America needed to get involved in World War I. So, with the help of one of the great Public Relations masters of all time, Edward Bernays, he created the Creel Commission, whose job was to change America’s mind.

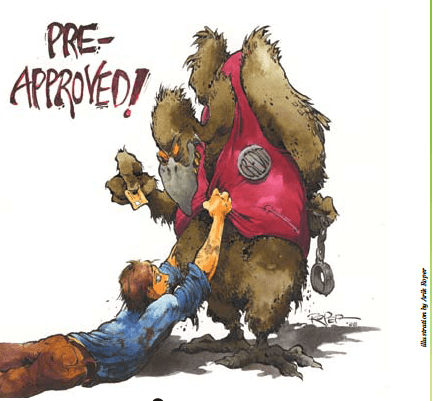

Bernays, like the many political propagandists who followed, honestly believed that the masses are just too stupid to make decisions for themselves – particularly when it involved global affairs or economics. Instead, an enlightened and informed elite (corporate America) needs to make the decisions, and then “sell” them to the public in the form of faux populist media campaigns. This way, the masses feel they are coming up with these opinions, themselves.

Truly populist positions, on the other hand – such as workers’ rights or minority representation – must be recontextualized as the corruption of the public by elite “special interests” or decadent social deviants. Throughout most of history, these scapegoats were the Jews, but now it’s mostly gays and liberals. By distracting the masses with highly emotionally charged issues like flag-burning or gay marriage, those in power consolidate their base of support while developing a new mythology of state as religion.

As long as they do all this, they don’t have to worry about how people vote, or what might be happening on the ground. “Unregulating” the mediaspace turns the fourth estate (the news agencies) into just another arm of the corporate conglomerates that fascism was invented to serve. (Mussolini called it “corporatism,” don’t forget.)

The last and most crucial step in creating a truly seamless fascist order, though, is to frighten the intellectuals, students, and artists from seeing the world as it is and sharing their sensibilities with one another. Hell, calling America’s leaders “a fascist regime” can’t be good for business. The only place I’m allowed to write this way is on my blog or here in Arthur – and neither pays the bills.

Besides: why rock the boat? I may not have the right to vote, anymore, but I’m being kept comfortable enough. Like others of my class, I have a roof over my head. I’m crafty enough to get paid now and again for a book or talk or comic series. And the state is functioning well enough that I can afford a tuna sandwich and walk around my neighborhood eating it without getting whacked with a rock or a grenade. As far as history goes, that’s pretty good.

So was democracy a failed experiment? Should we just let these guys run the country as long as they let us eat? Clearly, they’re not scared of us or what we might be saying about them. In fact, their best argument that we haven’t descended into fascism is the fact that we’re allowed to distribute columns like this one. How could we be living in a totalitarian propaganda state if there are articles pronouncing the same? Because fascism looks different every time around. 1930’s fascism failed because it was too obviously repressive. Today’s fascism works because it has turned the mediaspace into a house of mirrors where nothing is true and everything is permissible. The fact that there are plenty of blogs and even major books saying what’s happening and still it doesn’t matter is proof that it has worked.

But there is hope. It’s not just the radicals and militias who are alarmed, but mainstream congresspeople and government wonks. I, myself, have been approached by two separate government intelligence agencies and three members of congress (of both parties) for help understanding what they already deem to be actionable offenses against the American people by some of our leaders. They are disturbed by the disinformation campaign leading up to the Gulf War, voter fraud, and the way Americans have been frightened into supporting the curtailment of civil rights.

Surprisingly, most of my conversations with these patriotic people involve two main concerns. First, they have been ostracized by their peers for their views. This has created some urgency, for they fear they will not get enough party support for re-election if they don’t succeed in their efforts in the next few months. Second, and more troublingly, they are afraid to disillusion America’s youth. Isn’t there a way to fix this problem, they wonder, without raising an entire generation of Americans in environment of acknowledged voter nullification? And what of our reputation in the world? Which is more damaging to democracy: voter fraud, or the public awareness of voter fraud?

To this, we simply must conclude that the reality of voter fraud is more dangerous than any associated disillusionment. To worry about the impact on public consciousness is to get mired in the logic of public relations – and that’s what got us into this mess to begin with.

It’s time to get real, and either fight (through the courts, if possible) to reinstate the rule of law as established by the Constitution, or accept that Enlightenment-era democracy simply doesn’t work and move into a new phase of government by decree or market forces or whatever it is that comes next.

In any case, it serves no one to have a “pretend democracy” that’s actually something else. I’m going to stop denying what’s going on here, and use what influence I have with lawmakers, government workers, and activists to get them to do the same. Instead of trying to feel better about all this, I’m going to allow myself and everyone around me to feel worse.

Indeed, the bad news is the good news. Total disillusionment, though momentarily painful, is utterly liberating and probably required. Acceptance isn’t acquiescence at all; it’s the first step towards reconnecting with a reality that can and must be changed. If we’re going to get back on the horse, we’ve got to acknowledge that we’ve fallen off.