Originally published in Arthur No. 8 (Jan 2004):

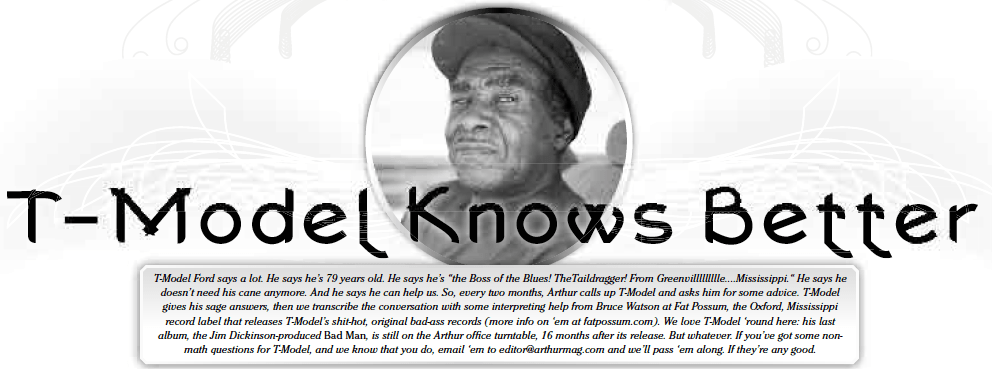

T-Model Ford says a lot. He says he’s 79 years old. He says he’s “the Boss of the Blues! The Taildragger! From Greenvillllllllle….Mississippi!“ He says he doesn’t need his cane anymore. And he says he can help us. So, every two months, an Arthur staffer calls T-Model and asks him about certain topics of the day. T-Model gives his answers over the phone, then we transcribe the conversation with some help from Bruce Watson at Fat Possum, the Oxford, Mississippi record label that releases T-Model’s one-of-a-kind blues albums (more info on ‘em at fatpossum.com). If you have any non-geography questions for T-Model, and we suspect that you do, email them to editorial@arthurmag.com

Arthur: T-Model one of our readers wrote in and said, “I’m worried about one of my longtime friends. He’s been hanging out with this woman who I know smokes crack. I’m afraid he’s going to start smoking crack too. What should I do?”

T-Model Ford: Well, be worried. If you like him, and he in it, best for you to stay away from him much as you can. Cuz you’ll get in trouble. You’ll be doin’ what he be doin’, or what the othern’ doin’. That crack helped cause a-many young people to mess up. I don’t know what it do, but some I hear say it mess the brains up. It must do somethin’ ‘cos they all want to fool with it. They wild, they don’t do right. They stay in trouble, meddlin’, breakin’ in, fightin’, do anything. I never seen none of it when [I was a young man], and I ain’t never smoked none of it. Now I done quit smokin’…quit about 20 years… I wouldn’t smoke another cigarette. Ain’t got no feeling for it. And I do good and I feeeel good. As old a man as I is, I’m still gettin’ up and goin’.

How can you tell when someone is on crack?

I seen some of ‘em since they done got way in it. Everywhere that smokin’ that crack got a good thing going, it breaks it up. Greenville looks like a ghost town now. You don’t see nothin’ hanging around. That crack? I hate to even see anybody smoking that mess. They don’t look right, they don’t act right. They look wild and stupid. If anybody smoke it, you can tell it. In the way they acts. Get on away from ‘em.

Is there anyway to get ‘em someone off of crack who‘s already in it?

Not hardly. Not ‘til they get in enough of a mess, then they have to get out of trouble.

Okay. Next question. One of our older readers writes in to say, “Dear T-Model, I thought I was a good father, my wife and I have been very loving, we have a beautiful daughter, she’s 15 years old, but we’re worried that she’s started to have sex.”

Uh-ohhhhh.

“She hasn’t admitted it to us, but we think it’s happening. We don’t know what to do. Should we leave her alone?”

Yes. Leave her alone. Cause next thing she’ll start sassin’ you, blessin’ YOU out, tellin’ you what you can’t do! What SHE can do! “I’m grown, I can do what I wanna do.” Blowin’ back. First thing you wanna hearin’. Seem you can’t raise your children now. You have to let ‘em go til they get their selves in trouble or mess up. Then they go to see anybody, but it be too late. They all do.

Is there a way for these parents to tell if their daughter is having sex? Can you tell?

Yeah, you can tell. Watch the breasts. They get sassy and nasty and … Once it get started, then let ‘em get their own place to stay. That’ll whoop ‘em quicker than anything! That’s right. They’ll find out they can’t. That a home’s where they at. It’s somethin’ else. You wanna go and get out like that, remember one thing gets turned over to the Good Lord. Ever where she head, let her go. She get into somethin’, don’t get her out, let her get out the hard way. Once she get out, she’ll make something out of herself.

A reader in his late teens writes, “Dear T-Model, I gotta buy a new car. I’m just drivin’ around town. I don’t need a truck. What should I look for? You got any suggestions on what kind of car I should get?”

If you gon’ do that, just to ride around in, find you an old model. The Lincoln, if it’s in good shape when you get it, take care of it, keep the oil changed and filter changed, and it’ll last a loooong time. Or a good Chevrolet or a good Ford or a good Buick.

You like those American cars.

Yes indeed. They all been good to me. They go longer. They last longer. And I had good safeties out of ‘em. I love ‘em. I got a ‘79 Lincoln here. It’s an antique, I want to buy an antique tag for it. It look good right now. Everybody’s trying to buy it. They want me to sell it. I told ‘em, It ain’t for sale. But still they want it. They like it.

Now, you know how to fix cars, right?

Well I can but I’m not able now, I done got broke up by that limb. Tree fell on me and I can’t get around. Before that tree fell on me, I’d work on and build motors and everything.

How did you learn how to do all that?

Go ‘round where people workin‘, and WATCH em. Watch em. I can’t read and write, can’t spell nothin’… but I never did carry my car to the shop.