(This article was originally written for Sci-Fi Universe magazine. After it was published there, a revised version was housed online at the now-defunct CrashSite. Here, pretty much, is the original SFU text. — Jay)

INVISIBLE(S) MAN

Or, Grant Morrison: The Man With the Post-Hypnotic Trigger Finger on the Throbbing Pulse of a Millennium-Long Battle for Control of Your Mind

by Jay Babcock

“The idea of comics is like sitting in front of your TV with a channel changer… Perception is a cut-up,” Grant Morrison said once.

As if to lend credence to his own statement, Morrison has been playing with our preconceptions of what comics published by the House of Superman could be about since he burst on the American comics scene with the hallucinatory Batman graphic novel Arkham Asylum. As part of the late- ’80s, post-Alan Moore new wave of British mainstream comics writers that included Sandman’s Neil Gaiman and fellow neo-psychedelicist Peter Milligan (author of DC’s Shade, the Changing Man), Morrison quickly made a name for himself by following up Arkham Asylum with several miniseries and one- shots, and an acclaimed, controversial run on DC’s Animal Man.

But it was with Morrison’s radical revamping of DC’s Doom Patrol that he really hit his stride, explicitly incorporating ideas historically foreign to mainstream superhero comics. Influenced by the work of Czech animator Jan Svankmajer, filmmakers Kenneth Anger and Maya Doren, mathematician Douglas Hofstadter, Morrison took what had been previously been billed as “the world’s most bizarre superheroes” at its word, giving the “heroes” real mental disabilities and sending them into strange new dimensions and situations that included encounters with the painting that ate Paris; evil Scissormen who speak in cut-up (“Defeating breadfruit in adumbrate” was a typical Scissorman sentence); the villainous Cult of the Unwritten Book; the Pale Police, who spoke exclusively in anagrams; the unforgettable Danny the Street, an extradimensional, sentient location with the spirit and sensibility of a transvestite; the Men From NOWHERE, “normalcy agents” whose mission was to “eradicate eccentricities, anomalies, and peculiarities wherever we find them”; and The Pentagon, which was seen, as one critic noted, as “headquarters of a bizarre supernatural conspiracy aiming to institute worldwide standardization and puritanical repression.”

It was a beguiling, bravura headrush, a seemingly improvised work of genius that spun further out of control each month. Morrison’s most amazing, hilarious creation in his three-plus years on Doom Patrol, though, was the Brotherhood of Dada, a villainous group that “celebrated the total absurdity of life” and campaigned against “consensus reality” in favor of “liberation, laughs, and libido.” The Brotherhood of Dada was headed by Mr. Nobody, a hilarious hipster prone to taunting the book’s heroes with statements like “There! We have now taken over the world. What are you going to do about THAT?” and asked, pointing to his team, “Are we not proof that the universe is a drooling idiot with no fashion sense?”

More than one Doom Patrol reader caught him or herself thinking the Brotherhood of Dada should have been the good guys. And, with his next major project, The Invisibles, Morrison essentially granted those fans their wish.

The Invisibles are a secret society devoted to subversion in all its forms, a group of revolutionary mysticist secret agents that includes characters codenamed King Mob (a bald assassin into the “fetish subculture”), Jack Frost (a teenage hooligan the group’s newest member, who is able to tap into a devastating psychokinetic power), Fanny (a transvestite witch), Boy (a female martial artist and former cop) and Ragged Robin (a psychic).

“Although we have a core group of characters, anyone can belong to or oppose the Invisibles,” Morrison explained in an introductory outline of the series. “Various ordinary and extraordinary folks [will be] drawn into a web of conspiracy that extends from the back streets of your hometown to the dark blue-green planet circling Alpha Centauri and beyond, out past the horizon of the spacetime supersphere itself, giving me the opportunity to tell stories ranging across time and genre, stories that will eventually come together and be revealed as one large-scale, shimmering holographic tapestry. This is the comic I’ve wanted to write all my life-a comic about everything: action, philosophy, paranoia, sex, magic, biography, travel, drugs,religion, UFOs… you can make your own list. And when it reaches its conclusion, somewhere down the line, I promise to reveal who runs the world, why our lives are the way they are and exactly what happens to us when we die.”

Ahem. Whatever his intentions, Morrison’s opening story arc was a stunner, chronicling the initiation of Jack Frost into the Invisibles by Tom O’Bedlam, a streetbum/magician who imparts wisdom like “There’s a palace in your head, boy; learn to live in it always” to Jack. In an interview with Sci-Fi Universe, Morrison talked about the source of inspiration for the pivotal sequence in which Jack is taught to “see” differently.

“When you’re a kid or teenager, you go on these long walks,” the Glasgow native says, “you just kinda drift off and wander through the city, and make these sort of mythological connections in your head. I’d been doing that, and I think most people do, but the Situationists [a loose group of ’60s radical intellectuals and artists] identified that as a revolutionary act, and that feeds straight into The Invisibles: the idea that you can make a ‘temporary autonomous zone,’ by impressing the imagination on the world in such a way that you create [it anew]. You’re walking through the city and if you want to see it-as Raoul Vaneigem says in The Revolution of Everyday Life, my favorite Situationist text-as ‘some fabulous city of dreams,’ all it takes is a way of looking.”

For Morrison, this act of imagination is intensely political. “I really think the ‘political process’ doesn’t work and always leads to the same thing, which is the mountain of heads in the Enlightenment, which we explored in the first book of The Invisibles,” he says. “I think that there’s not much in the world that I can actively, effectively change, except what happens within the boundaries of my own skin [which I do] through whatever, by following magical processes or obscure therapists like Wilhelm Reich.

“I really believe if you do change yourself, then it has a vital effect. If you put out good ideas instead of bad ideas… good connections instead of bad ones.

“I get kinda of evangelical about it, sometimes,” says Morrison, laughing, “but it can work.”

Despite the anarchist underpinnings of The Invisibles, the series’ opening story arc attracted the attention of BBC Scotland, who have commissioned Morrison to adapt that arc into a six-part, three-hour TV series intended for broadcast on network television in late 1997 or 1998.

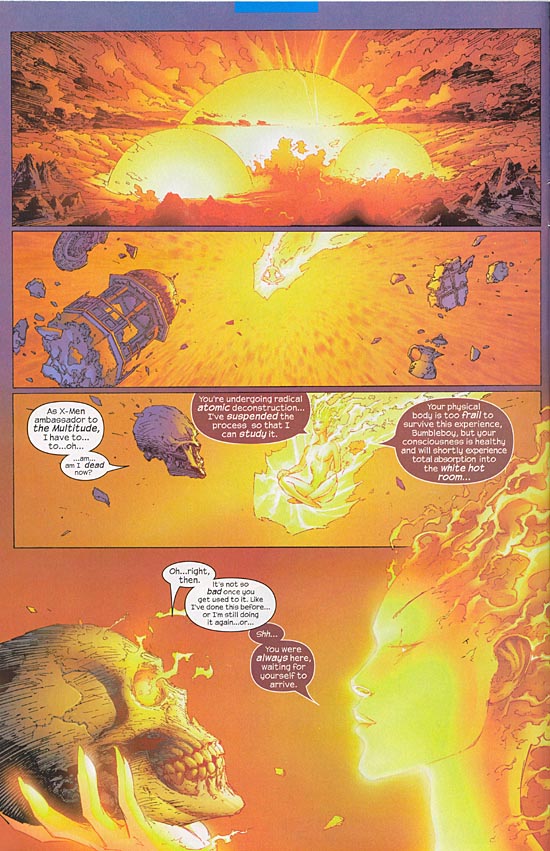

Meanwhile, The Invisibles comic has continued in typical Morrison style. Plot and stylistic twists seemed to issue from the writer’s fevered brain in torrents. If the stories seemed to run on a logic of their own, becoming an occasionally indecipherable catalog of ’90s zeitgeist with a plot that was almost a meta-deus ex machina, we didn’t care-we were just happy to be along for the dizzying, delirious ride. Allusions to The Prisoner, A Clockwork Orange, and the work of transgressive Italian filmmaker Pier Pasolini and techno-pagan-neo-Learyite theorist Terence McKenna came fast and often; historical figures like Lords Byron and Shelley and the Marquis de Sade appeared-and co-starred-with the team; and the stories were filled with voodoo priests, reform houses, magical signs of the “dark emperor Mammon,” the enemy’s special agents called Myrmidons, “psychic early warning systems,” post-hypnotic triggers, cyphermen and gnostic engineers.

With a radical storyline and even more radical storytelling, The Invisibles was bound to be a challenging read, and eventually the series found itself at the brink of cancellation due to dropping sales.

“We confused a few people with the first book,” Morrison now admits. “Also, it seemed to turn off the American readers because it was set in Britain for most of the time.”

So, The Invisibles-Volume One ended, and on Christmas, 1996, Volume Two debuted, complete with a new cover artist, fan favorite Brian Bolland, a new interior art team (Phil Jiminez and John Stokes), and, at least for the opening story arc, a new setting-the American Southwest-and a more straightforward storytelling style.

“I’d planned to do this anyway in the second year, but when we came to it, I thought we should take this opportunity to start a second volume,” explains Morrison. “The first four issues of Volume Two are this complete ironic version of The Invisibles for America. Because they’re in America, we’re getting a whole different version of the Invisibles. But in issue five, we actually see the reality of it. There’s a big time-travel story that’s going on within this… and that leads into more of the stuff that people are familiar with from the first book. I think hopefully if we can drag in some more of the casuals with the sex and violence at the start, then we can lead them up to the more sophisticated stuff.

“I can’t really do The Invisibles the way I did it before because ‘Arcadia’ [a complex, time-travel story arc involving the Marquis de Sade and the French Enlightenment] just didn’t work. That’s when everyone jumped off the book. And I had to be forced to admit that there’s certain things that the general comics audience just can’t handle. I have to downscale from that, slightly, so there won’t be those same kind of complex historical things again.

“Still, starting in issue seven, there will be a three-parter which explain all the things that came up in Paris in 1924…and so that will be the whole Futurist thing and Dada. So hopefully, I’ll be able to sneak more of the historical stuff in.

“And I’m still into some real, real, real weird far-out stuff being done by some of the magicians in America. I’ve got something called The Voodoun Gnostic Workbook and it’s by a guy Michel Bertiaux, he’s the head of this cult in Chicago. It’s science fiction stuff and they’re doing it, they’re living it, y’know, they’re doing all kinds of things to mutate themselves into a post-human species. It’s the furthest out stuff I’ve ever read in magic and I want to get into a bit more of that. But I do have to keep [everything] a bit more straightforward, I think, because I lost everyone.”

“The core thing everything comes back to, again, is that if you change yourself, you can change reality. And that’s a stupid ‘New Age’ idea, but…[it’s also] ‘as above, so below’-the hermetic philosophy thing. The character that runs a thread right through The Invisibles-who’s the core of it-is Jack Frost. He starts off as a completely rough kid, he’s nothing, and we follow this guy as he develops into a future buddha, and we see how that affects the entirety of everything.

“I’m trying to do something with a kind of fractal, holographic effect, and even the tiniest parts of The Invisibles refract the whole shape of it.

“I have it all mapped out. I know what happens in the last one. It will finish in the year 2000, which is where it was meant to, maybe a little later in the year than I expected. I think that after that, it won’t work. I’m tapping into all of these currents [aliens, conspiracy, paranoia, mysticism, millennialism], but I think once we get past that year 2000 threshold, and even slightly before it, I think we’ll be where the modernists were at the end of the last century. And what we’ll get is a completely different spirit and these apocalyptic, millennial spirits will transform really quickly into something else. So I don’t want to still be doing the apocalyptic digest paranoid conspiracy book when there’s a new current out in the world. I want it set up so The Invisibles will end, so I can come up with something new that will hopefully embody or whatever the forward-looking spirit we start to get.”

As anti-conventional as Morrison’s comics are, sometimes they seem to pale in comparison to the very public lifestyle he has led over the last few years-one marked by world travel, partying with Britpop bands like the Boo Radleys, massive hallucinogen ingestion, self-education in the arts of various magics, and, last year a frightening brush with death involving blood poisoning, a severely infected lung, and a (temporary) stress-related giant abscess on the side of his face. All of these experiences have made their way into his adult-oriented comics work.

“The last issue of the Doom Patrol was written on mushrooms,” Morrison says proudly,” and I did an entire 64-page story for 2000 A.D. on Ecstasy. I did it cuz it was kinda what the strip was about, it was a ‘two people getting off and taking drugs and going to a rave in the future’- sort of thing. And I thought I wanted to get into that a bit, so I took a couple of Es and just wrote the whole thing out.

“There’s a trip scene in issue two of The Invisibles where they’re up on a mesa. That’s actually real and the dialogue is taken from a tape-recorded conversation.

“And I’ve done automatic writing, trance writing and I always write down my dreams,” he adds. “But I don’t do it as much now. I think I’ve just gotten better at shutting down the conscious personality and letting the comics write themselves, so it’s become even more fun for me. I can take a backseat and know that this stuff generates itself almost. I’ve been doing it long enough now that it’s kinda easy.”

Morrison’s interest in music -“I listen to music all the time when I’m working, and I even put lines in if I happen to hear a line and I’m writing a script”, he says-was combined with his love for comics, musclemen and hallucinogens in 1996’s Flex Mentallo four-issue DC miniseries, a work of probable genius that weaved multiple mobius loops of narrative logic involving superheroes, has-been rock stars, nostalgia, creativity, mythology and mind-altering drugs, beautifully rendered by Frank Quitely.

“That was one of my favorite things that I’ve ever done, it sorta summed things up for me, but no one bought it,” says an obviously disappointed Morrison. “It didn’t sell, no one knew about it, it was really badly promoted, no one got to see the art before it was released. It was a whole catalogue of disasters, really, cuz I think it was a great comic, but it was one of those great comics that no one really has a feel for. So that kind of put me off from doing that kind of thing. That was as far out as I’m likely to go with superheroes.”

Of course, Morrison is still doing superhero comics, but, like Alan Moore, Morrison now segregates his “adult” work [The Invisibles] from the “kids” work [DC’s Aztek and the phenomenally successful Justice League of America] he does that actually pays the rent.

“What I’m doing with JLA and Aztek is going back to the kind of stuff I liked when I was a kid and trying to do an updated version of it for kids’ now,” Morrison explains.

“But my main focus is The Invisibles. I’m not really trying to do anything for the ages,” he says modestly, “I’m just trying to reflect the immediacy of these times and put it out to other people and make that connection and hope that then maybe they’ll do something and send it back to me, and create a network of good ideas.”