Via Max Milgram…

[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 8] “Forgetting and Remembering the Instructions of the Land” by Freeman House (1996)

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the eighth lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

This piece was delivered as the Rufus Putnam Lecture at the Ohio University, April 24, 1996. Parts of this lecture have been published in Martha’s Journal and in Raise the Stakes.

Forgetting and Remembering the Instructions of the Land: The Survival of Places, Peoples, and the More-than-human

by Freeman House

I: Forgetting

Maps are magical icons. We think of them as pictures of reality, but they are actually talismans that twist our psyche in one direction or another. Maps create the situation they describe. We use them hoping for help in finding our way around unknown territory, hoping they will take us in the right direction. We are hardly aware that they are proscribing the way we think of ourselves, that they are defining large portions of our personal identities. With a world map in our hands, we become citizens of nations. We become Americans, Japanese, Sri Lankans. With a national map in front of us, we locate ourselves in our home state; we become Ohioans or Californians. Unfolding the road map on the car seat beside us, we become encapsulated dreamers hurtling across a blurred landscape toward the next center of human concentration. Even with a topographical map, the map closest to being a picture of the landscape, we are encouraged to describe our location by township, range, and section—more precise, more scientific, we are told, than describing where we are in terms of a river valley or mountain range.

When Rufus Putnam’s Ohio Company acquired its part of the Northwest Territories, the first thing General Putnam did, perhaps before he had even seen all of it, was to draw squares on a map—townships, quarter-sections, long sections. Putnam was, after all, a surveyor and a land developer. Those blue lines on maps that are now yellow with age set in motion a process of systematic forgetfulness which may just now be reaching its culmination. As precisely as if he were using a scalpel, the general was separating the new human inhabitants from the sensual experience of their habitat. The new lines brought with them a quality of perception, one that randomly separated waterways from their sources. They fragmented the great forests before a single tree was cut.

If the landscape was a radio, in 1787 the volume began to be turned down on the channel that had carried the messages of the other creatures and the plants and the winds and waters full blast for thousands of years of ’round-the-clock broadcasting. People had been living in southern Ohio for millennia before the good general arrived, and there is every indication they were able to hear what the landscape was telling them. They experienced themselves as a part of the landscape that lay between themselves and the horizon. The landscape and the other creatures in it had a voice within their hearts and minds. Their maps were in the form of stories that carried down through the generations information about where and when the food plants were at their best, information about the seasonal migration routes of other species — species that might be important for either food or communion. The stories told of seasonal cycles — planting times, flood years, birth control. But as far as we know, no maps. And most certainly no maps with straight lines on them.

President Jefferson would soon instruct his surveyors the length and breadth of the enormous Louisiana Purchase to do the same thing—and with the best of intentions. Map it; divide it up by township, range, and section. It was a management problem. Breaking up the nearly unimaginable breadth of the newly acquired lands into tidy grids would make possible their orderly occupation by the yeoman farmer democrats who resided at the heart of Jefferson’s vision for the new world. This was the first step into bringing order to a sprawling wilderness, spreading its use peacefully among a rapidly encroaching population in a society where the engine of order was commerce. Political thinking of the time (as it still is) was driven by John Locke’s idea that the primary function of government is the protection of property. If the government was to have something to govern, it needed to turn all that land into property.

The technique had its benefits. Smaller grids provided for the establishment of instant towns and villages, centers of commerce and transportation. The larger grids, for sale at a dollar an acre, provided space for pioneer trappers and farmers to provide the amenities necessary for the growth of a new society. American civilization established itself with startling efficiency and rapidity. The previous inhabitants were startled right out of a culture that had evolved for thousands of years in equilibrium with the life processes surrounding. Too often, they were startled right out of their skins.

But the system had unanticipated side effects which we are only beginning to understand in the last 30 years, as we have discovered something called the environment. Continue reading

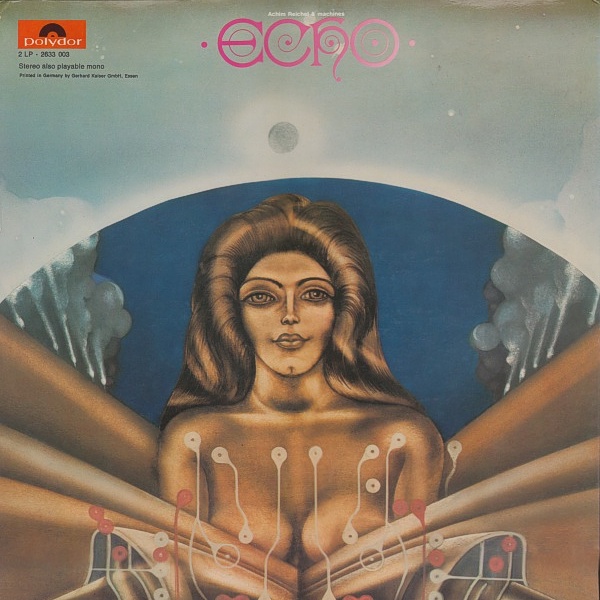

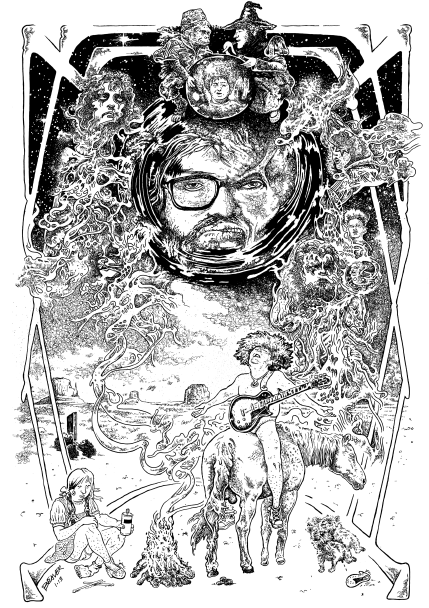

WIZARDS OF OZMA: Stewart Voegtlin and Beaver on MELVINS’ heaviest record (Arthur, 2013)

As originally published in Arthur No. 34 (April 2013)…

WIZARDS OF OZMA

What made MELVINS’ 1992 beercrusher Lysol the most unlikely religious record ever built? STEWART VOEGTLIN pays attention to the men behind the curtain…

Illustration by BEAVER

Discussed:

Melvins

Lysol

Boner Records, 1992

Melvins

Gluey Porch Treatments

Alchemy Records, 1989

Melvins

Ozma

Boner Records, 1987

Melvins

Eggnog

Boner Records, 1991

Earth

Extra-Capsular Extraction

Sub Pop, 1990

Melvins

Joe Preston

Boner Records, 1992

Thrones

Alraune

The Communion Label, 1996

Used to fight flu in early 1900s. Used as douche, disinfectant, “birth-control agent.” Toxic to birds, fish, and aquatic invertebrates. But commonly consumed by alcoholics as alternative to more expensive tipple. Taken off grocer’s shelf. Popped open. Sprayed into its cap. Thrown back. Used and reused because—or in spite of—its overpowering carbolic taste worsened with a burn weaponized and wince inducing. And, finally, used, infamously—but not orally—by Buzz Osborne (guitar, vocals), Joe Preston (bass), and Dale Crover (drums) as title of Melvins’ fourth full-length record, Lysol, released in 1992.

Lysol is Melvins’ biggest record. It’s their heaviest. While being “big” and “heavy,” Lysol inadvertently questions what exactly constitutes “big” and “heavy” records. While being intentionally cryptic, Lysol questions what it means for records to be unintentionally accessible, and why a record’s content must posit a “message” that not only means something, but also purports to uncover some semblance of truth. The dialectic is reluctant. That it’s as “big” and “heavy” as the record itself, and actually does threaten to posit a “message” that masquerades as truth, is an unexpected payoff from a record that satisfies as many aesthetic criteria as it eliminates.

Harold Bloom could’ve been talking about Lysol when he praised the completeness and finality of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. The book fulfilled Bloom’s idea of the “ultimate western.” All genre criteria were not only satisfied; they were eliminated. Anything published on its heels was not a western at all, but futility in the form of mechanics, ink, paper. Lysol was released in 1992; the two “heaviest” records released that year other than itself are Black Sabbath’s Dehumanizer and Eyehategod’s In the Name of Suffering. Their sound is distinct. They work within the confines of their carefully cultivated worlds, and thrive in doing so. Lysol’s sound? Also distinct. Also works within its world. But does so in such manner that the construction that defines its world falls, like a ladder kicked away after its ascendant looks down on what they’ve climbed out of, and becomes not meaningless, but too meaningful.

What Melvins accomplish with Lysol, particularly its 11-minute opener, “Hung Bunny,” is a sort of Heavy Metal as religious music. When “Hung Bunny” isn’t stomping inchoate distillations of “God’s silence,” it’s spreading śūnyatā out as endless horizon. When “Hung Bunny” isn’t indifferent about “theophany,” it’s providing the conditions necessary to understand, or receive, the divine in the first place. Not surprisingly, it’s an attentive record. A concentrated record. A ceremonial record. It’s the most unlikely religious record ever built, as its cover tunes (which account for half of the program) easily constitute the band’s bulletproof belief system, while “Hung Bunny,” recreates Tibetan Buddhism’s ritual music, and stillbirths one of the more unfortunate subgenres, “stoner doom,” without even taking a toke.

It’s a risky hyperbole. (Aren’t they all?) Somewhere in a suburban basement, a kid’s pulling tubes, crushing beers, Lysol spraying through ear-wilting wattage. It may not initially present as enigma, even in the midst of buzz, but it will always require interpretation. How that kid understands Lysol may be no different than how orthodox monks understand the Jesus prayer. In a deceptively simple way, the kid and the monk make sense of their lives through external power, with or without what Richard Rorty calls “an ambition of transcendence.” That we struggle, unprovoked, through these self-imposed puzzles, is what binds us, despite the disparity of aesthetics we are geared towards through fate’s random generation. Ultimately we gravitate towards that which lends our lives meaning—even if meaning is undone in its meaninglessness. Realizing the kid’s and the monk’s “road” to sense is the same path carved out by, and because, of the “big” and the “heavy” is the first step out onto the yellow brick.

Continue reading[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 7] “DREAMING INDIGENOUS: One hundred years from now in a northern California valley” by Freeman House

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the seventh lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

This piece was first published in Summer 1992 on the sesquicentennial of Columbus’ landing on North America in the Journal of the Society for Ecological Restoration.

DREAMING INDIGENOUS

One hundred years from now in a northern California valley

by Freeman House

Contact between whites and natives didn’t happen here in my part of North America until 150 years ago, which makes it easier to think like this. You can still see enough of the earlier patterns in the landscape to be able to guess at what it looked like then. Once contact did happen, however, it proceeded with unrelenting fury. Within a seven-year period ending in 1862, the 10,000-year-old culture that had been so wonderfully adapted to this little tuck in the Coast Range was reduced to a few broken individuals hanging on locally and a handful more isolated from the source of their identity, bereft of home on the reservation a hundred miles away.

Life was pleasant for the whites, in a rough sort of way. For a hundred years or so, pleasant enough so that even now some cowboys look back on that time as the very peak of existence. It was the usual scene for the North American West: a few steers and dairy cows, some hogs for market, and an economic boom every 30 or 40 years to keep things interesting—and growing. The tanbark boom kept quite a few of the boys busy for a time. And even though the oil boom fizzled, it brought the aura and glamor of the great world into the valley for a while, and Petrolia got a hotel. Come the bust, as it always did, well, subsistence was not so bad, with salmon and venison steak to fall back on.

The really big boom, the one that makes you wonder if anyone will survive the bust, came as a windfall to the handful of large landowners. A whole slew of events, historical and technological, had conspired to make the ubiquitous Douglas-fir worth something, worth a lot, after decades of laying it down around the edges of the prairies and burning over it year after year to expand the pasture. Three quarters of the landscape was suddenly marketable after three generations of living well enough off the other one quarter.

It came out fast—90 percent of three quarters of 300 square miles of timber from some of the most erodible forest slopes in North America, all in the space of a single generation. No one paid any attention to what anyone else was doing. There was no awareness, really, that a whole watershed was being stripped of its climax vegetation all at once. For most of the years between 1950 and 1970, several mills were kept running ‘round the clock, and the trucks taking timber out of the valley were so numerous and frequent that their drivers had to agree on one route out and another one in. There was a lot of money; anyone could find a job who wanted one. The schoolteacher worked at the sawmill at night.

Two 100-year storms within a ten year period was bad luck, they said, coming at a time when so many acres of soil were exposed to the sky. But exposed they were, and a vast warm rain on top of an unusually heavy snowpack on the ridges sent thousands of tons of sediment into the creeks and then into the river. In one week in 1955, the structure of the river was altered completely, from a cold, stable, deeply channeled waterway enclosed and cooled by riparian vegetation to a shallow, braided stream with broad cobbled floodplains, warm in summer, flashy in winter. And then it happened again in 1964.

When the new homesteaders began to arrive in the early 1970s, all we knew was that the king salmon and the silver salmon were almost gone. A few of us tried to do something about it, and by 1981 had established a sort of volunteer cottage industry in salmon propagation. We learned quickly that the key to the restoration of wild populations was habitat, and we found ourselves creating jobs along with volunteer and educational programs in reforestation, in erosion control. One thing leads to another—now we hear ourselves talking landscape rehabilitation, watershed restoration planning, water quality monitoring,

We were only vaguely aware that we were engaged in something called environmental restoration, and it wasn’t until the Restoring the Earth conference in Berkeley in 1988 that we realized that we were part of a planet-wide movement. Even before that, however, we had become aware of some of the pitfalls of this new terrain of consciousness. Logging was still a part of the essential economy of our valley. It was happening on nowhere near the scale of the bad old days, and practices had improved considerably thanks to well-reasoned timber harvest rules established during the Jerry Brown administration, but ecological systems were still being disrupted in ways not clearly understood. As we became more skilled in repairing damaged areas, we became aware of the danger of becoming the source of cheap janitorial services for corporate industry and others that might be opening up new wounds even as we were attempting to heal the old ones. It was not enough to become expert in putting back together what had been torn apart. Unless we adopted the cause of local ecological reserves, unless we tried to educate ourselves against destructive land use practices and tried to prevent them when education failed, unless we helped establish new small-scale resource extraction industries rooted in the ethic of ecosystem health, we were in danger of becoming Roto-Rooter persons for a dysfunctional society. If we practiced environmental restoration out of the same short-term assumptions that had created the disturbances in the first place, where could we end but as apologists for new deserts? Even the Roto-Rooter man tells the homeowner to stop pouring bacon grease down the toilet!

We are now concerned with the cultural content of the next 150 years because our experience tells us we must be. A successful sustainable human culture is a semi-permeable membrane between nature and human society, with information flowing freely in both directions. Having put ourselves in the way of some of the physical data coming toward us from the natural world, we are given both the rationale and the imperative for our roles in social transformation. Having perceived the reciprocal relationship between natural systems and local cultures, we have little choice but to work to make the latter more adaptive, more indigenous.

* * *

In making my contribution to this collection of restorationists’ reflections on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ landing, I will allow myself two assumptions: that profound cultural shifts can happen suddenly and at any time; and that we are now in the midst of a pivotal era that offers us chances to abandon our more deadly economic practices, and begin to seek ways to adapt—and survive.

Because indigenous culture is always a response to locale, I will paint an imaginary picture of some aspects of life in our little valley 100 years from now. I will take a look at how a future might look if the insights available to one environmental restorationist were available to everyone. I will portray a future where timber, fish, and ranching are still the mainstays of economic life because I wish it to be that way; any other alternative seems less attractive. And for the treeplanter who is irritated by heady abstractions—who asks little more, after all, than for good work unfreighted with ambivalence—I will focus on some of the workaday themes of everyday life.

I will speak to you now from the future.

Continue reading

SUNDAY AFTERNOON LISTENINGGGGGGGGGGG

REEEEINCARNATION

A Poem from Joshua McDermott

Before things got difficult for my family,

I complained one Christmas morning

when I didn’t get the toy I wanted.

My mother had actually bought it for me,

but she hid it in the closet

to see how I’d react.

Later, when there were no toys,

when there wasn’t even a closet,

when my mother had died,

the snow on the ground outside

was enough.

Joshua Lew McDermott is a 23 year old poet from Idaho. He sometimes lives in Logan, Utah, where he organizes readings and independently publishes his friends’ work. He has two cats, reads a lot of anarchistic books, and likes to go hiking. “

DAILY REMINDER

[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 6] “More Than Numbers: Twelve or Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Watershed” by Freeman House

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the sixth lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

This piece was first published in the Spring 2001 edition of Northern Lights. It is also featured in the 2010 anthology Working the Woods, Working the Sea: An Anthology of Northwest Writing, edited by Jerry Gorsline and Finn Wilcox and published by Empty Bowl Press of Port Townsend, Washington.

MORE THAN NUMBERS

Twelve or Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Watershed

by Freeman House

(with apologies to Wallace Stevens)

1.

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing.

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

It’s December again and curdled aluminum cloud cover extends all the way to where it kisses the iron of the ocean horizon. At its mouth, the river runs narrow and clear. If you’ve lived through many winters here, the sight is anomalous; normal December flows are more likely bank to bank, and muddy as corporate virtue. A storm had delivered enough wetness around the time of Hallowe’en to blast open the sand berm that separates the river from the sea all summer and fall. The salmon had been waiting and they came into the river then.

All through November and December the jet stream has been toying with us, diverting Pacific storms either to the north or south. The fish have been trapped in pools downstream, waiting for more rain to provide enough flow to move them up 50 or 60 miles to their preferred spawning habitat. By now many of the gravid hens will have been moved by the pressure of time and fecundity to build their egg nests, called redds, in the gravels in the lower ten miles of the river. Come true winter storms, too much water is likely to move too much cobble and mud through these reaches for the fertile eggs to survive. The redds will be either buried under deep drifts of gravel or washed away entirely.

I have committed the restorationist’s cardinal sin. I have allowed myself a preferred expectation of the way two or more systems will interact. For the last two winters, steady pulses of rain have created flows that were good for the migrating salmon, carrying them all the way upstream before Solstice, but a desultory number of fish had entered the river those years. This year, from all reports, the ocean is full of salmon, more than have been seen in 20 years. So I have allowed myself the fantasy of a terrific return combined with excellent flows.

I know better than to hope for conditions that fit my notion of what’s good. Perhaps as a reaction to my wishful thinking and its certain spirit-dampening consequences, I am suffering from a certain diminution of ardor.

2.

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

It marked the edge

Of one of many circles.

I am suffering from diminished ardor. As I look out the window on the hour-long drive to Cougar Gap [1], I am seeing the glass half-empty. As my eyes wander the rolling landscape, they seek out the raw landslides rather than indulging my usual glass-half-full habit of comparing what I’m seeing with my memory of last year’s patterns of new growth on the lands cut over 40 years ago.

It’s one of the skills you gain in 20 years of watershed restoration work—to see the patterns in the landscape and be able to compare them with a fairly accurate memory of what was there last year. I’ve come to believe that I have restored in myself a pre-Enlightenment neural network that interprets what the eyes see, what the ears hear, what the skin feels in terms of patterns and relationships rather than as isolated phenomena numeralized so that they can be graphed. It’s a skill given little credibility in the world of modern science, but it’s deeply satisfying nonetheless.

Among the raw scars on the landscape to which my eye is drawn today, some are the result of human activities and some are the natural processes of a very wet, earthquake-prone, sandstone geology. Their patterns don’t change that much from year to year; the soil that would allow them to recover rapidly has been washed off the steep slopes and into the river. It’ll take hundreds if not thousands of years for that soil to rebuild itself. It’ll take generations for the mud in the river to be flushed out to sea.

These are patterns with cycles longer than the individual human life. It’s satisfying and useful to be cognizant of them, too. Such knowledge tempers our human tendency to want to fix—read tamper with—everything in sight.

Continue reading

Robert Fripp – “Silent Night” a la Frippertronics (1979)

Via ILM…