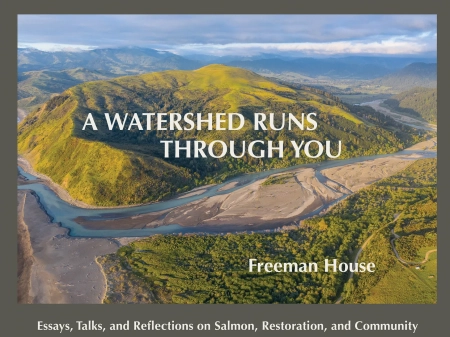

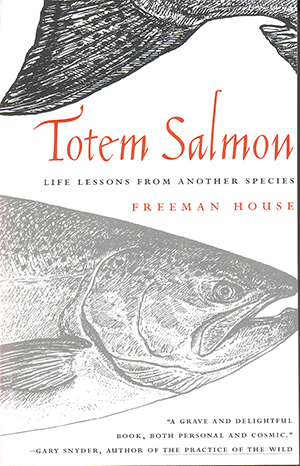

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

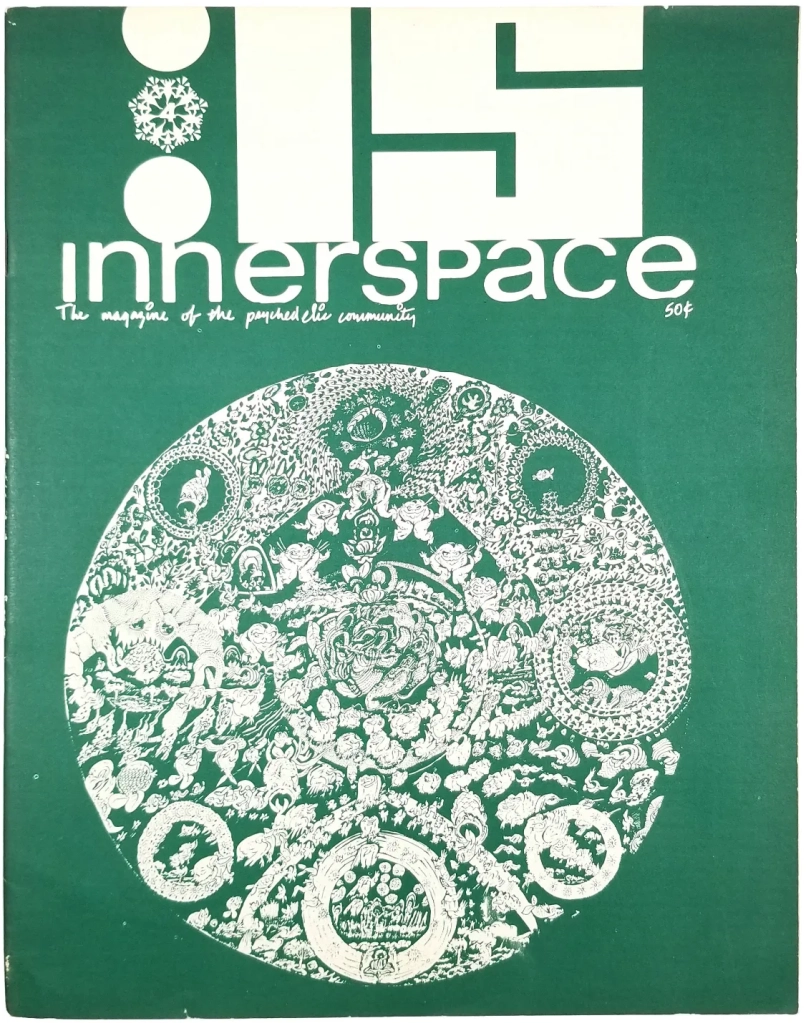

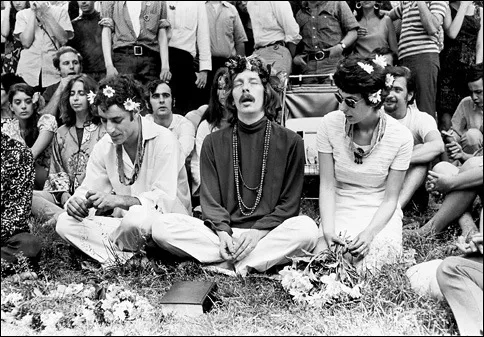

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the seventh lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

This piece was first published in Summer 1992 on the sesquicentennial of Columbus’ landing on North America in the Journal of the Society for Ecological Restoration.

DREAMING INDIGENOUS

One hundred years from now in a northern California valley

by Freeman House

Contact between whites and natives didn’t happen here in my part of North America until 150 years ago, which makes it easier to think like this. You can still see enough of the earlier patterns in the landscape to be able to guess at what it looked like then. Once contact did happen, however, it proceeded with unrelenting fury. Within a seven-year period ending in 1862, the 10,000-year-old culture that had been so wonderfully adapted to this little tuck in the Coast Range was reduced to a few broken individuals hanging on locally and a handful more isolated from the source of their identity, bereft of home on the reservation a hundred miles away.

Life was pleasant for the whites, in a rough sort of way. For a hundred years or so, pleasant enough so that even now some cowboys look back on that time as the very peak of existence. It was the usual scene for the North American West: a few steers and dairy cows, some hogs for market, and an economic boom every 30 or 40 years to keep things interesting—and growing. The tanbark boom kept quite a few of the boys busy for a time. And even though the oil boom fizzled, it brought the aura and glamor of the great world into the valley for a while, and Petrolia got a hotel. Come the bust, as it always did, well, subsistence was not so bad, with salmon and venison steak to fall back on.

The really big boom, the one that makes you wonder if anyone will survive the bust, came as a windfall to the handful of large landowners. A whole slew of events, historical and technological, had conspired to make the ubiquitous Douglas-fir worth something, worth a lot, after decades of laying it down around the edges of the prairies and burning over it year after year to expand the pasture. Three quarters of the landscape was suddenly marketable after three generations of living well enough off the other one quarter.

It came out fast—90 percent of three quarters of 300 square miles of timber from some of the most erodible forest slopes in North America, all in the space of a single generation. No one paid any attention to what anyone else was doing. There was no awareness, really, that a whole watershed was being stripped of its climax vegetation all at once. For most of the years between 1950 and 1970, several mills were kept running ‘round the clock, and the trucks taking timber out of the valley were so numerous and frequent that their drivers had to agree on one route out and another one in. There was a lot of money; anyone could find a job who wanted one. The schoolteacher worked at the sawmill at night.

Two 100-year storms within a ten year period was bad luck, they said, coming at a time when so many acres of soil were exposed to the sky. But exposed they were, and a vast warm rain on top of an unusually heavy snowpack on the ridges sent thousands of tons of sediment into the creeks and then into the river. In one week in 1955, the structure of the river was altered completely, from a cold, stable, deeply channeled waterway enclosed and cooled by riparian vegetation to a shallow, braided stream with broad cobbled floodplains, warm in summer, flashy in winter. And then it happened again in 1964.

When the new homesteaders began to arrive in the early 1970s, all we knew was that the king salmon and the silver salmon were almost gone. A few of us tried to do something about it, and by 1981 had established a sort of volunteer cottage industry in salmon propagation. We learned quickly that the key to the restoration of wild populations was habitat, and we found ourselves creating jobs along with volunteer and educational programs in reforestation, in erosion control. One thing leads to another—now we hear ourselves talking landscape rehabilitation, watershed restoration planning, water quality monitoring,

We were only vaguely aware that we were engaged in something called environmental restoration, and it wasn’t until the Restoring the Earth conference in Berkeley in 1988 that we realized that we were part of a planet-wide movement. Even before that, however, we had become aware of some of the pitfalls of this new terrain of consciousness. Logging was still a part of the essential economy of our valley. It was happening on nowhere near the scale of the bad old days, and practices had improved considerably thanks to well-reasoned timber harvest rules established during the Jerry Brown administration, but ecological systems were still being disrupted in ways not clearly understood. As we became more skilled in repairing damaged areas, we became aware of the danger of becoming the source of cheap janitorial services for corporate industry and others that might be opening up new wounds even as we were attempting to heal the old ones. It was not enough to become expert in putting back together what had been torn apart. Unless we adopted the cause of local ecological reserves, unless we tried to educate ourselves against destructive land use practices and tried to prevent them when education failed, unless we helped establish new small-scale resource extraction industries rooted in the ethic of ecosystem health, we were in danger of becoming Roto-Rooter persons for a dysfunctional society. If we practiced environmental restoration out of the same short-term assumptions that had created the disturbances in the first place, where could we end but as apologists for new deserts? Even the Roto-Rooter man tells the homeowner to stop pouring bacon grease down the toilet!

We are now concerned with the cultural content of the next 150 years because our experience tells us we must be. A successful sustainable human culture is a semi-permeable membrane between nature and human society, with information flowing freely in both directions. Having put ourselves in the way of some of the physical data coming toward us from the natural world, we are given both the rationale and the imperative for our roles in social transformation. Having perceived the reciprocal relationship between natural systems and local cultures, we have little choice but to work to make the latter more adaptive, more indigenous.

* * *

In making my contribution to this collection of restorationists’ reflections on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ landing, I will allow myself two assumptions: that profound cultural shifts can happen suddenly and at any time; and that we are now in the midst of a pivotal era that offers us chances to abandon our more deadly economic practices, and begin to seek ways to adapt—and survive.

Because indigenous culture is always a response to locale, I will paint an imaginary picture of some aspects of life in our little valley 100 years from now. I will take a look at how a future might look if the insights available to one environmental restorationist were available to everyone. I will portray a future where timber, fish, and ranching are still the mainstays of economic life because I wish it to be that way; any other alternative seems less attractive. And for the treeplanter who is irritated by heady abstractions—who asks little more, after all, than for good work unfreighted with ambivalence—I will focus on some of the workaday themes of everyday life.

I will speak to you now from the future.

Continue reading →