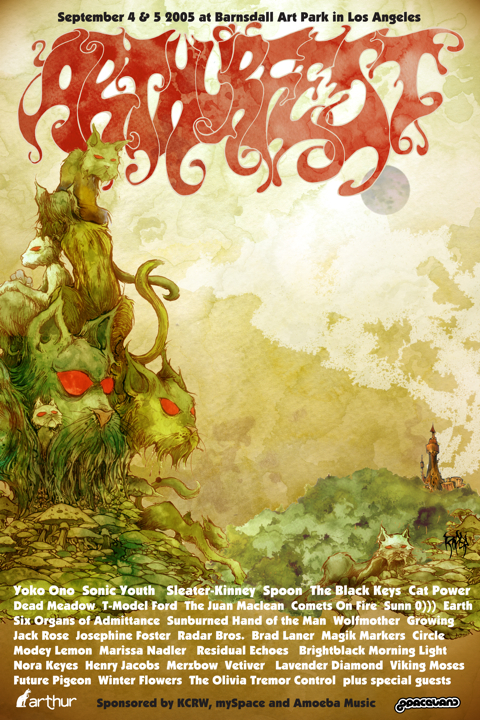

Encounter With Maximon

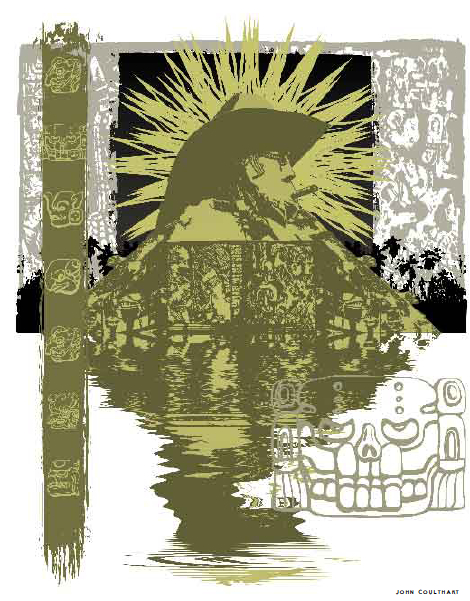

While investigating Guatemala’s folk-magic patron saint of thieves and whores, James Marriott made a serious mistake. Illustration by John Coulthart.

Originally published in Arthur No. 8 (Jan 2004)

The first children I asked to show me the way to the house of Maximon, Guatemala’s ‘evil saint’, turned tail and fled. The next boy I approached was unable to escape, hobbled by a pair of oversized rubber boots, and pointed me in the right direction. The building wasn’t much to look out—unpainted concrete blocks with a corrugated iron roof—but once I was in I knew I’d come to the right place.

Maximon sat at one end of a dark room, the life-sized dummy of a moustachioed white man wearing a suit, sunglasses, a felt hat and a silk scarf, with a garish handkerchief over his mouth. Candles were arrayed before him, and towards the entrance, at the opposite end of the room, tarot and palm readings were taking place. Another doorway led through to a courtyard, beyond which was a shop selling cigars, magical potions, herbs, candles and anything else the devotee might need.

There was a fire in the courtyard, around which a Mayan woman with gold teeth, a ladino woman and two boys of around six hyperventilated on huge cigars, working themselves into a sweat. The Mayan woman offered to read my palm. When I foolishly declined, she shrieked with laughter and returned to the serious business of her cigar. The ladino woman didn’t even look at me—Maximon is the patron saint of thieves and prostitutes, but I couldn’t very well ask her if either of these applied—and when the nicotine-crazed boys started to run around my legs, I went back into the main room to take a seat at the back and make myself as inconspicuous as possible.

New arrivals would walk straight past the tarot readers and into the courtyard, where they consulted with the Mayan woman before puffing on cigars and preparing themselves for a consultation with the saint. They would then approach the impassive figure and speak to him, stroking his arms and laying money and other offerings in a bowl in his lap. A smartly dressed man standing by the saint appeared to be his keeper, putting offerings of cigars in his mouth and tipping aguardiente, a fiery local spirit, down his wooden throat, or gently lashing the devotees with a bundle of herbs during a limpia, or soul cleansing.

The children came in, one looking demonic as he threatened the other with a bottle, then tied his feet together with a length of twine. The keening victim tried to hide behind me, crawling into a safe position sheltered by the gringo as the increasingly demented bully giggled and made throat-slitting gestures, the pain and anguish in his victim’s face only spurring him on to greater fury. For a terrible moment I thought that I was mistaken—they weren’t children at all, but rather stunted adults, their growth arrested by heavy nicotine use—but the pitch of the victim’s whine reassured me. As the bullying grew nastier in tone, I wondered if I should intervene, but it seemed patronizing to do anything— the only attention the other adults paid was to motion to the weaker child to be quiet. Eventually the bully left the room, and his charge fled. It seemed a fitting introduction to the world of the Judas of the Western Highlands.

* * *