Tag Archives for occult

"Form is the Graveyard of Conciousness" – Frank Haines opening at Lisa Cooley

Occultist artist Frank Haines debuts an installation of new paintings, sculptures, and situations tonight at the Lisa Cooley, located at 54 Orchard Street in Chinatown. Most of tonight’s work was made in the gallery space, utilizing a wide range of formlessness and abstraction. With heavy Theosophical influence, the exhibition invokes themes of duality, including one energetic sculpture of two two-tone dangling equilateral triangles. Also well known for his experimental music as one half of the duo Blanko and Noiry, Haines is offering attendees of tonight’s show first crack at a cassette tape limited to 500 of never-before heard music he created while studying in Austria.

If Haines’ style reminds you of Kenneth Anger, you’re not alone. Haines will present a new performance entitled Blood Transfusion for a Ghost at the Anger exhibition at PS1 June 20th.

The show runs from tonight to July 3rd. More of Haines’ art is featured here and here.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46zaCPZRlio

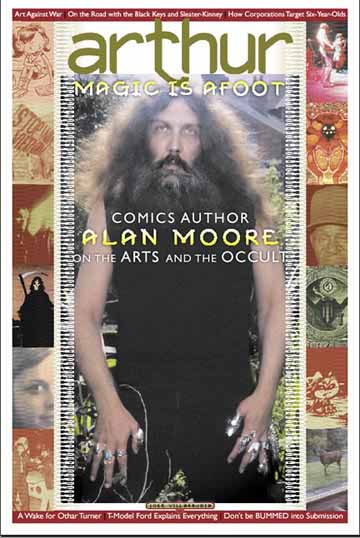

MAGIC IS AFOOT: A Conversation with ALAN MOORE about the Arts and the Occult (Arthur, 2003)

Originally published in Arthur. No. 4 (May 2003)

Cover photograph by Jose Villarrubia. Art direction by W.T. Nelson.

Magic Is Afoot

Celebrated comics author ALAN MOORE gives Jay Babcock a historical-theoretical-autobiographical earful about the connection between the Arts and the Occult

Gen’rals gathered in their masses/Just like witches at black masses/Evil minds that plot destruction/Sorcerer of death’s construction/In the fields the bodies burning/As the war machine keeps turning/Death and hatred to mankind/Poisoning their brainwashed minds”

— Black Sabbath, “War Pigs” (1970)

As author Daniel Pinchbeck pointed out in Arthur’s debut issue last fall, magic is afoot in the world. It doesn’t matter whether you think of magic a potent metaphor, as a notion of reality to be taken literally, or a willed self-delusion by goggly losers and New Age housewives. It doesn’t matter. Magic is here, right now, as a cultural force (Harry Potter, Buffy, Sabrina, Lord of the Rings, the Jedi, and of course, Black Sabbath) , as a part of our daily rhetoric, and perhaps, if you’re so inclined, as something truly perceivable, in the same way that love and suffering are real yet unquantifiable–experienced by all yet unaccounted for by the dogma of strict materialism that most of us First Worlders say we “believe“ in. Magic is here.

It’s the season of the witch. And arguably the highest-profile, openly practicing witch–or magus, or magician, or shaman–in the Western world is English comics author Alan Moore. You may know Moore for the mid-’80s comic book Watchmen, a supremely dark, exquisitely structured mystery story he crafted with artist Dave Gibbons that examined, amongst other things, superheroes, Nixon-Reagan America, the “ends justify the means” argument and the nature of time and space. Watchmen was a commercial and critical success, won numerous awards, and made the tall, Rasputin-like Moore a semi-pop star for a couple of years. Watchmen re-introduced the smiley face into the visual lexicon, the clock arrow-shaped blood spatter on its face studiously washed off by the late-’80s/early ‘90s rave scene. Rolling Stone lovingly profiled Moore; he guested on British TV talkshows; he was mobbed at comics conventions; and he got an infamous mention in a Pop Will Eat Itself song.

Recoiling in horror from the celebrity status being foisted on him, Moore withdrew from public appearances. He also withdrew from the mainstream comics industry, bent on pursuing creative projects that had little to do with fantasy-horror and science fiction and adult men with capes. Some of these projects, like the ambitious Big Numbers, fell apart; others were long-aborning sleeper successes that took years to produce, like From Hell (Moore and artist Eddie Campbell’s epic Ripperology), Voice of the Fire (Moore’s stunning first novel) and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (a clever Victorian pulp hero romp in comics form, drawn by Kevin O’Neill); and still others were good-faith genre comics efforts to pay the rent and restore certain storytelling standards to a genre (superhero comics) in decline.

In recent years, Moore’s public profile has been rising again, partly due to the embrace of Hollywood. This summer will see the release of the second high-profile film based on an Alan Moore comic series in three years: a $100-million film version of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, starring Sean Connery. But like the Hughes Brothers’ 2001 radically simplified, arthouse/Hammer adaptation of From Hell starring Johnny Depp and Heather Graham, League will only have some surface similarity to the comics work that inspired it. That’s down as much to typical Hollywood machinations as much as the sheer unadaptability of Moore’s comics–these are works meant to function as comics. Even Terry Gilliam couldn’t see a way to make a film out of Watchmen. Moore’s comics are as tied to the peculiar, wonderful attributes of the comics form as possible.

Comics is itself where the magic comes in. The comics medium is one of the few mainstream entertainment industries open to folks who are openly into what is considered to be very weird, spooky and possibly dangerous stuff. Alejandro Jodorowsky, best known for the heavily occultist films El Topo and Holy Mountain, has been happily doing comics in France for decades. The English-speaking comics industry, meanwhile, has always been open to these sorts of people; indeed, Steve Moore (no relation) and Grant Morrison had been doing magic long before Alan Moore’s late-1993 foray into magical practice. Comics, it seems, attracts–or breeds–magicians, and magical thinking. Perhaps it’s that the form–representational lines on a surface–is directly tied to the first (permanent) visual art: the paintings on cave walls in what were probably shamanistic, or ritualistic settings. In other words: magical settings. Understood this way, comics writers and artists’ interest in magic/shamanism seems almost logical.

For Alan Moore, as the conversation printed below makes clear, this stuff isn’t just the stuff of theory or history or detached anthropological interest. It’s his reality. It informs his daily life. And it informs his artistic output, which in recent years, has been a prodigious outpouring of comics (his ongoing Promethea series, ingeniously drawn by J.H. Williams III, is by far the best), prose essays, “beat seance” spoken-word recordings and collaborative magical performances–one of which, a stunning multimedia tribute to William Blake, I was lucky enough to witness in London at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in February 2000. I did not get to meet Alan Moore at that performance, but I was able to interview him later that year by telephone. We talked for two and a half hours. Rather, Alan talked and I made occasional interjections or proddings. What I found is that Alan doesn’t speak in whole sentences. He doesn’t speak in whole paragraphs. He speaks in whole, fully-formed essays: compelling essays with logical structure, internal payoffs, joking asides, short digressions and strong conclusions. Reducing and condensing these enormously entertaining and enlightening lectures proved not only structurally impossible, but ultimately undesirable. So here are thousands upon thousands of words from Mr. Moore, with few interruptions, assembled from that first marathon in June 2000 and a second in November 2001. Don’t worry–these conversations are not out-of-date. They were ahead of their time. Their time is now.

Because Black Sabbath told us only half the story. There are other, largely forgotten purposes for magic…

Arthur: How did your interest in becoming a magician develop? How has being a magician affected how you approach your work?

Alan Moore: Brian Eno has remarked that a lot of artists, writers, musicians have a kind of almost superstitious fear of understanding how what they do for a living works. It’s like if you were a motorist and you were terrified to look under the bonnet for fear it will go away. I think a lot of people want to have a talent for songwriting or whatever and they think Well I better not examine this too closely or it might be like riding a bicycle–if you stop and think about what you’re doing, you fall off.

Now, I don’t really hold with that at all. I think that yes, the creative process is wonderful and mysterious, but the fact that it’s mysterious doesn’t make it unknowable. All of our existences are fairly precarious, but mine has been made considerably less precarious by actually understanding in some form how the processes that I depend on actually work. Now, alright, my understanding, or the understanding that I’ve gleaned from magic, might be correctly wrongheaded for all I know. But as long as the results are good, as long as the work that I’m turning out either maintains my previous levels of quality or, as I think is the case with a couple of those magical performances, actually exceeds those limits, then I’m not really complaining.

Arthur: You work mostly in comics, which is interesting, as so many magicians–maguses? magi?–have been involved in the visual arts in the last century. Austin Osman Spare, Harry Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren. Aleister Crowley did paintings and drawings.

Crowley lamented that he wasn’t a better visual artist. I went to an exhibition of his and well, some of the pictures work just because they’ve got such a strange color sense, but…it has to be said that the main item of interest was that they were by Crowley. But yes, there’s that whole kind of crowd really: Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, Harry Smith. And if you start looking beyond the confines of self-declared magicians, then it becomes increasingly difficult to find an artist who wasn’t in some way inspired either by an occult organization or an occult school of thought or by some personal vision.

Most of the Surrealists were very much into the occult. Marcel Duchamp was deeply involved in alchemy. “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors”: that relates to alchemical formulae. He was self-confessedly, he referred to it as an alchemical work. Dali was a great many things, including a quasi-fascist and an obvious scatological nutcase, but he also was involved deeply in the occult. He did a Tarot deck. A lot of the Surrealists were taking inspiration from alchemical imagery, or from Tarot imagery, because occult imagery is perhaps a natural precursor of a lot of the things that the Surrealists were involving themselves with.

But you don’t have to look as far as the Surrealists, really. With all of those neat rectangular boxes, you’d think Mondrian would be rational and mathematical and as far away from the Occult as you could get. But Mondrian was a Theosophist. He [borrowed] the teachings of Madame Blavatsky–all of those boxes and those colors were meant to represent theosophical relationships. Annie Besant, the Theosophist around the turn of the last century, published a book where she had come up with the idea, novel at the time, that you could represent some of these abstract energies that Theosophy referred to by means of abstract shapes and colors. There were a lot of people in the art community who were keeping up upon ideas from the occult and theosophy, they immediately read this and thought, Gosh you could, couldn’t you? And thus modern abstract art was born.

One of the prime occult ideas from the beginning of the last century, which is also interesting because it was a scientific idea, and this was the sudden notion of the fourth dimension. This became very big in science around the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th, because of people like these eccentric Victorian mathematicians like Edwin Abbot Abbot–so good they named him twice–who did the book Flatland, and there was also C. Howard Hinton, who was the son of the close friend of William Gull, he gets a kind of walk-on in From Hell, who published his book, What is the Fourth Dimension?

And so ‘the fourth dimension’ was quite a buzzword around the turn of the last century and you got this strange meeting of scientists and spiritualists because the scientists and the spiritualists both realized that a lot of the key phenomena in spiritualism could be completely explained if you were to simply invoke the fourth dimension. Two woods of different materials, two rings of wood, different sorts of wood, but at seances could become interlocked. Presumably. This was some sort of so-called stage magic. The idea of the fourth dimension could explain that — how could you see inside a locked box? Or a sealed envelope? Well in terms of fourth dimension, you could. Just as sort of three-dimensional creatures can see the inside of a two-dimension square. They’re looking down on it through the top, from a dimension that two-dimensional individuals would not have.

So you got this surreal meeting of science and spiritualism back then, and also an incredible effect upon art. Picasso spent his youth pretty well immersed in hashish and occultism. Picasso’s imagery where you’ve got people with both eyes on one side of their face is actually an attempt to, it’s almost like trying to create, to approximate, a fourth dimensional view of a person. If you were looking at somebody from a fourth dimensional perspective, you’d be able to see the side and the front view at once. The same goes with Duchamp’s “Nude Descending A Staircase” where you’ve got this sort of multiple image as if the form was being projected through time, as it descends the staircase.

The further back you go, the more steeped in the occult the artists become. I’ll admit to you, this is looked at from an increasingly mad perspective on my part, but sometimes it looks to me like there’s not a lot that didn’t come from magic. Look at all of the musicians. Gustav Holst, who did The Planets? He was working according to kabbalistic principles, and was quite obsessed with Kabbalah. Alexander Scriabin: another one obsessed with Kabbalah. Edward Elgar: He had his own personal vision guiding him, much like Blake had got. Beethoven, Mozart, these were both alleged, particularly Mozart, were alleged to belong to Masonic occult organizations. Opera was entirely an invention of alchemy. The alchemists decided that they wanted to design a new art form that would be the ultimate artform. It would include all the other artforms: it would include song, music, costume, art, acting, dance. It would be the ultimate artform, and it would be used to express alchemical ideas. Monteverdi was an alchemist. You’ve only got to look at the early operas, and see just how many of them are about alchemical themes. The Ring. The Magic Flute. All of this stuff, there’s often overt or covert alchemical things running through it all.

And there’s Dr. Dee, himself. One of the first things he did, he used to do special effects for performances. He got a reputation for being a diabolist just through doing…I suppose it was a kind of 14th-century Industrial Light and Magic, really. He came up with some classical play, which required a giant flying beetle. He actually came up with a giant flying beetle! [laughs] I think that did more to get him branded as a diabolist than any of his later experiments in angels. No one could understand all this stuff that he was doing with the Enochian tables–they weren’t really bothered by that. But he’d made a man shoot up into the air! [laughter] So he must be the devil or something…

Given the sheer number of people from all fields that would seem to have a magical agenda, it’s even more strange that magic is generally held in such contempt by any serious thinkers. I think that most people that would think of themselves as serious thinkers would tend to assume that anybody in Magic must be some kind of wooly headed New Age mystical type that believes every horoscope that they read in the newspaper. That would be completely dismissive of giving the idea of Magic any intellectual credibility. It’s strange–it seems like you’ve got a world where most of our culture is very heavily informed by Magic but where we almost have to keep up the pretext that there isn’t any such thing as magic, and that you’d have to be mad to be involved in it. It’s something for children or Californians or other New Age lunatics. That seems to be the perception and yet once you only scratch the surface in a few areas, you find that magic is everywhere.

Continue reading