Some of the items still available at the store…

Author Archives for Jay Babcock

FADE TO BROWN

Because so many people have been asking for some clarification as to Arthur’s future:

There are no further issues of Arthur planned at this time. We’re happy we got to do the three issues we did in 2013, while being able to pay our contributors for the first time ever and fulfill all those old outstanding subscriptions.

The online mail-order Arthur Store will be open until March 2, 2014. At that point, all unsold backstock will be chucked on the compost heap or into the recycle bin. Everything has been discounted. A number of items are now sold out and have been removed from the Store. Go here to grab stuff for cheep: arthur.bigcartel.com

This website, as well as the Arthur Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr pages/feeds, will stop being updated on March 3, 2014.

For many reasons, it’s now time for Arthur to go dormant. Perhaps the mag will sprout again in the future, perhaps not. In any event, we hope we’ve been of some use, and thank everyone who’s been so kind to us.

Thank you so kindly,

The Arthur Gang

Joshua Tree, CA * Portland, Ore. * Austin, TX * Northampton, MA * wherever you can hear your footsteps

(Artwork by Arik Roper)

EVERYTHING MUST GO

Arthur store CLOSES for good on March 2, 2014 and everything left goes in the recycle bin or compost heap.

CDs have been discounted to $5 each, and prices for many back issues of the magazine have been cut as well.

[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 11] “Watershed Work in a Changing World: Lessons Not Yet Learned” by Freeman House

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons From Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the eleventh (and final) lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11.

Watershed Work in a Changing World: Lessons Not Yet Learned

by Freeman House

Plenary presentation for the California Salmon Restoration Federation’s 25th Annual Conference, Santa Rosa, CA, 9 March 2007

Watershed restorationists tend to develop a peculiar set of mind. Community-based watershed groups, the heart of anything we might call a popular movement toward restoring the Earth, are particularly prone to these psychological symptoms. The accepted protocols encourage us to envision something called “reference ecosystems,” some ideal state of dynamic equilibrium that we are then encouraged to imagine existed once and toward which we should be devoting our efforts. We develop strong attachments to certain elements of the living places in which we work, different elements for different practitioners. Some people love fish and some love trees. Many of us love the whole mysterious web of interrelationships. In all, we act as if the distribution of species and communities and weather patterns—either in the present or in our idealized reference ecosystem — is the once and always way that nature has manifested itself.

Sooner or later, we discover the weaknesses in such an idea. If only by paying attention long enough, we discover that nature over the long term is as fluid and fickle as running water. Recently, researching the prehistory of my region, I discovered something that changed the way I thought of the systems in which I’d been working for more than 20 years. I found that only five to six thousand years ago, the entire bioregion had been a few degrees warmer than it has been since and those few degrees determined a very different distribution of species than those we have been striving to maintain for so long. Most relevant for me was the discovery that in that warmer time that followed the last period of glaciation, there had been few if any salmon using the waters of California. (I found this discovery to be slightly embarrassing, having made public statements which confused the history of salmon speciation with the time that salmon had been using my home river. I would tell people salmon had been using my river for 60,000 years rather than the more accurate 6,000.)

More fascinating, though, is the archaeological evidence of Karuk and Tsnungwe ancestral peoples in the mountains above the Trinity River more than eight thousand years ago. Peoples living today in the Klamath River systems are direct descendants of people who lived through climate changes similar in magnitude to the ones we anticipate now. While those ancient peoples had centuries to adapt to a more gradual change than we anticipate, the degree to which that culture changed its life ways remains instructive. In simple terms, the Karuk people changed the way they lived. They changed from scattered groups of hunter-gatherers living in the mountains and following the food to substantial village cultures with an elaborate ceremonial life organized around newly available acorn and salmon resources. The point here is that a people completely changed their way of life in response to changes in the environment and they did it successfully and sustainably. The scope of change we face is quite different; it’s getting warmer rather than cooler and the rate of change is likely to be much quicker. We may be able to draw no more instruction from the Karuk model than that we adopt similar goals—to change our ways of life in the direction of sustainability and survival. Even James Lovelock, that most gloomy of prognosticators, ends a recent interview that predicts the human species pushed back into the Artic zones with the cheery observation that we are all survivors of humans who have endured half a dozen climate changes of equal magnitude within human time.

Now, you might ask, what does all this philosophizing have to do with how community-based watershed restorationists carry on their work? Climate change models currently available are projected on a global scale with an infinitude of possible local variations. Watershed restoration is by definition a local effort. How can community-based watershed groups include the unknown variables that face us as we make our strategic plans?

Continue reading[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 10] “Citizens and Denizens” by Freeman House

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the tenth lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

Citizens and Denizens

by Freeman House

Keynote talk for the first Carmel Watershed festival, 2004

I’ve been asked to talk on the subject of watershed citizenship. That made me want to know more about that word citizen, so I dug around a little. It’s been a useful exercise. The word originated as “denizen,” meaning ‘of a place.’ As urban life became more dominant, denizen evolved into “citizen” meaning city person. As nations rose, the word came to define who belonged inside the boundaries and who didn’t. The ancient Greeks reserved the rights and privileges of citizenship to wealthy men, and for most of Roman times, they were dispensed at the pleasure of the emperor. It wasn’t until the American and French revolutions that the notion of popular and participatory decision-making came to be associated with the word. So we can trace the concept from ancient tribal and ethnic definitions of who does and who doesn’t belong to “our” society, forward in time as it evolves toward more inclusiveness. But always there is the notion of boundaries….. In the natural world, boundaries are rarely so clear as humans have been able to make them. (What grizzly or salamander would have invented the rectangular grid? The boundaries of, say, Idaho represent the range of what?)

As the word is used today, “citizen” is the creature of the invented world, rather than a participant in unfolding creation, which is what a denizen might be.

Continue readingTHE ERA

HFS: SPOT is sharing his photos from the Black Flag/Minutemen/SST era. Like this shot from Black Flag’s infamous Pollywog Park gig:

Info on this stash, and dozens more photos, about half with with captions: http://www.spotinator.com/

[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 9] “The Case For The Watershed As An Organizing Principle” by Freeman House

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the ninth lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

The Case For The Watershed As An Organizing Principle

by Freeman House

[I’ve rarely given a talk in circumstances more alien to my life experience. This talk was presented a roomful of county and state bureaucrats charged with implementing a five-county wetlands protection and restoration effort. The five counties were the southwestern-most part of California, stretching from Santa Barbara to San Diego, a part of the state that makes me feel like I’m in a foreign country. As if to accentuate the weirdness, the luncheon was held at Sea World, a theme park in San Diego.]

I’ve had quite a bit of time to puzzle about what qualifies me to be here. I feel a little like a visiting diplomat or more accurately, an anthropologist dropping into a whole other culture. Up in the backwoods of northern California, where I come from, we tend to think of ourselves as living in Alta California. Los Angeles and San Diego seem like another place, although they shouldn’t, considering that the voters around here determine a lot of what goes on in the state of California. Which is where I live regardless of the fact that it’s much easier for me and my comrades to think of ourselves as part of the Klamath Province.

I have worked at watershed restoration for 20 years, but in a drainage where there are no dams, and where there are still three species of a wild salmon population holding on. An eighth of the land base is managed benignly by the federal government as the King Range National Conservation Area, another eighth not so benignly by corporate timber interests, and the rest is held either in ranches or private smallholdings. It has a human population density of less than ten folks per square mile. Not too many similarities. And most of the people in this room probably know more about wetlands biology than I do.

Since it was a book I wrote that inspired the organizers to invite me and the book, Totem Salmon, is mainly about attempts to invoke a new (or rather very old) kind of community identity that lives within the constraints and opportunities of the place it finds itself, that’s what I’ll go ahead and talk about.

It could be my best credentials for being here today is the fact that I was born in Orange County. The earliest memories are of my first five years spent at my grandparents’ home in Anaheim, pre-Disneyland. Set in the middle of town, I had two acres to run in haphazardly planted to oranges and lemons and avocados, and for a long time that Edenic space was my model for paradise. Each weekend, we’d drive in my grandfather’s 1935 Buick sedan for maybe ten minutes to a local farm to buy our week’s supply of eggs and milk and vegetables. When we extended our drive to visit Aunt Florence in Pomona, we drove through 60 unbroken miles of commercial orange groves, another image of paradise. I’m revealing my age when I tell you that the air was wonderful, the light incredible.

Since then, I’ve learned something about the settlement of contemporary Anaheim. The existence of Anaheim is entirely dependent on 19th-century amateur efforts in social and physical engineering. Hard as it may be to believe when trying to find the freeway exits to Anaheim today, it was largely settled in the 1860s by polyglot groups of urban utopians who had few of the skills required for the kinds of agriculturally-based communitarian paradigms they were pursuing.

One thing was clear to all of them, however, and that was that their dreams were dependent on importing water to the arid lands they hoped would support them. Continue reading

SONNY

Via Max Milgram…

[SUNDAY LECTURE NO. 8] “Forgetting and Remembering the Instructions of the Land” by Freeman House (1996)

“Freeman House is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than 25 years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the biographical note for Freeman House on the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Innerspace, a mid-1960s independent press magazine for the nascent psychedelic community; presided over the marriage of Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967; and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers.

This is the eighth lecture in this series. This series ran previously on this site in 2010-11, and is being rerun now because it’s the right thing to do.

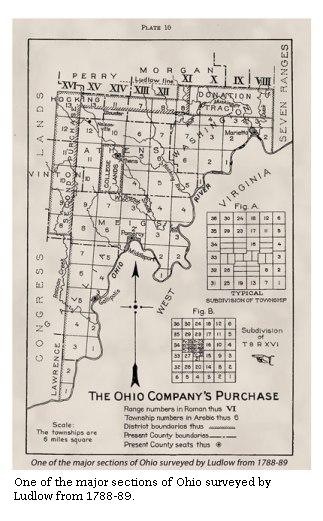

This piece was delivered as the Rufus Putnam Lecture at the Ohio University, April 24, 1996. Parts of this lecture have been published in Martha’s Journal and in Raise the Stakes.

Forgetting and Remembering the Instructions of the Land: The Survival of Places, Peoples, and the More-than-human

by Freeman House

I: Forgetting

Maps are magical icons. We think of them as pictures of reality, but they are actually talismans that twist our psyche in one direction or another. Maps create the situation they describe. We use them hoping for help in finding our way around unknown territory, hoping they will take us in the right direction. We are hardly aware that they are proscribing the way we think of ourselves, that they are defining large portions of our personal identities. With a world map in our hands, we become citizens of nations. We become Americans, Japanese, Sri Lankans. With a national map in front of us, we locate ourselves in our home state; we become Ohioans or Californians. Unfolding the road map on the car seat beside us, we become encapsulated dreamers hurtling across a blurred landscape toward the next center of human concentration. Even with a topographical map, the map closest to being a picture of the landscape, we are encouraged to describe our location by township, range, and section—more precise, more scientific, we are told, than describing where we are in terms of a river valley or mountain range.

When Rufus Putnam’s Ohio Company acquired its part of the Northwest Territories, the first thing General Putnam did, perhaps before he had even seen all of it, was to draw squares on a map—townships, quarter-sections, long sections. Putnam was, after all, a surveyor and a land developer. Those blue lines on maps that are now yellow with age set in motion a process of systematic forgetfulness which may just now be reaching its culmination. As precisely as if he were using a scalpel, the general was separating the new human inhabitants from the sensual experience of their habitat. The new lines brought with them a quality of perception, one that randomly separated waterways from their sources. They fragmented the great forests before a single tree was cut.

If the landscape was a radio, in 1787 the volume began to be turned down on the channel that had carried the messages of the other creatures and the plants and the winds and waters full blast for thousands of years of ’round-the-clock broadcasting. People had been living in southern Ohio for millennia before the good general arrived, and there is every indication they were able to hear what the landscape was telling them. They experienced themselves as a part of the landscape that lay between themselves and the horizon. The landscape and the other creatures in it had a voice within their hearts and minds. Their maps were in the form of stories that carried down through the generations information about where and when the food plants were at their best, information about the seasonal migration routes of other species — species that might be important for either food or communion. The stories told of seasonal cycles — planting times, flood years, birth control. But as far as we know, no maps. And most certainly no maps with straight lines on them.

President Jefferson would soon instruct his surveyors the length and breadth of the enormous Louisiana Purchase to do the same thing—and with the best of intentions. Map it; divide it up by township, range, and section. It was a management problem. Breaking up the nearly unimaginable breadth of the newly acquired lands into tidy grids would make possible their orderly occupation by the yeoman farmer democrats who resided at the heart of Jefferson’s vision for the new world. This was the first step into bringing order to a sprawling wilderness, spreading its use peacefully among a rapidly encroaching population in a society where the engine of order was commerce. Political thinking of the time (as it still is) was driven by John Locke’s idea that the primary function of government is the protection of property. If the government was to have something to govern, it needed to turn all that land into property.

The technique had its benefits. Smaller grids provided for the establishment of instant towns and villages, centers of commerce and transportation. The larger grids, for sale at a dollar an acre, provided space for pioneer trappers and farmers to provide the amenities necessary for the growth of a new society. American civilization established itself with startling efficiency and rapidity. The previous inhabitants were startled right out of a culture that had evolved for thousands of years in equilibrium with the life processes surrounding. Too often, they were startled right out of their skins.

But the system had unanticipated side effects which we are only beginning to understand in the last 30 years, as we have discovered something called the environment. Continue reading

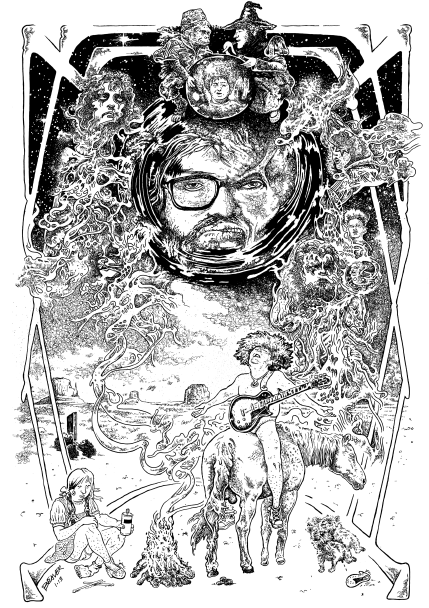

WIZARDS OF OZMA: Stewart Voegtlin and Beaver on MELVINS’ heaviest record (Arthur, 2013)

As originally published in Arthur No. 34 (April 2013)…

WIZARDS OF OZMA

What made MELVINS’ 1992 beercrusher Lysol the most unlikely religious record ever built? STEWART VOEGTLIN pays attention to the men behind the curtain…

Illustration by BEAVER

Discussed:

Melvins

Lysol

Boner Records, 1992

Melvins

Gluey Porch Treatments

Alchemy Records, 1989

Melvins

Ozma

Boner Records, 1987

Melvins

Eggnog

Boner Records, 1991

Earth

Extra-Capsular Extraction

Sub Pop, 1990

Melvins

Joe Preston

Boner Records, 1992

Thrones

Alraune

The Communion Label, 1996

Used to fight flu in early 1900s. Used as douche, disinfectant, “birth-control agent.” Toxic to birds, fish, and aquatic invertebrates. But commonly consumed by alcoholics as alternative to more expensive tipple. Taken off grocer’s shelf. Popped open. Sprayed into its cap. Thrown back. Used and reused because—or in spite of—its overpowering carbolic taste worsened with a burn weaponized and wince inducing. And, finally, used, infamously—but not orally—by Buzz Osborne (guitar, vocals), Joe Preston (bass), and Dale Crover (drums) as title of Melvins’ fourth full-length record, Lysol, released in 1992.

Lysol is Melvins’ biggest record. It’s their heaviest. While being “big” and “heavy,” Lysol inadvertently questions what exactly constitutes “big” and “heavy” records. While being intentionally cryptic, Lysol questions what it means for records to be unintentionally accessible, and why a record’s content must posit a “message” that not only means something, but also purports to uncover some semblance of truth. The dialectic is reluctant. That it’s as “big” and “heavy” as the record itself, and actually does threaten to posit a “message” that masquerades as truth, is an unexpected payoff from a record that satisfies as many aesthetic criteria as it eliminates.

Harold Bloom could’ve been talking about Lysol when he praised the completeness and finality of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. The book fulfilled Bloom’s idea of the “ultimate western.” All genre criteria were not only satisfied; they were eliminated. Anything published on its heels was not a western at all, but futility in the form of mechanics, ink, paper. Lysol was released in 1992; the two “heaviest” records released that year other than itself are Black Sabbath’s Dehumanizer and Eyehategod’s In the Name of Suffering. Their sound is distinct. They work within the confines of their carefully cultivated worlds, and thrive in doing so. Lysol’s sound? Also distinct. Also works within its world. But does so in such manner that the construction that defines its world falls, like a ladder kicked away after its ascendant looks down on what they’ve climbed out of, and becomes not meaningless, but too meaningful.

What Melvins accomplish with Lysol, particularly its 11-minute opener, “Hung Bunny,” is a sort of Heavy Metal as religious music. When “Hung Bunny” isn’t stomping inchoate distillations of “God’s silence,” it’s spreading śūnyatā out as endless horizon. When “Hung Bunny” isn’t indifferent about “theophany,” it’s providing the conditions necessary to understand, or receive, the divine in the first place. Not surprisingly, it’s an attentive record. A concentrated record. A ceremonial record. It’s the most unlikely religious record ever built, as its cover tunes (which account for half of the program) easily constitute the band’s bulletproof belief system, while “Hung Bunny,” recreates Tibetan Buddhism’s ritual music, and stillbirths one of the more unfortunate subgenres, “stoner doom,” without even taking a toke.

It’s a risky hyperbole. (Aren’t they all?) Somewhere in a suburban basement, a kid’s pulling tubes, crushing beers, Lysol spraying through ear-wilting wattage. It may not initially present as enigma, even in the midst of buzz, but it will always require interpretation. How that kid understands Lysol may be no different than how orthodox monks understand the Jesus prayer. In a deceptively simple way, the kid and the monk make sense of their lives through external power, with or without what Richard Rorty calls “an ambition of transcendence.” That we struggle, unprovoked, through these self-imposed puzzles, is what binds us, despite the disparity of aesthetics we are geared towards through fate’s random generation. Ultimately we gravitate towards that which lends our lives meaning—even if meaning is undone in its meaninglessness. Realizing the kid’s and the monk’s “road” to sense is the same path carved out by, and because, of the “big” and the “heavy” is the first step out onto the yellow brick.

Continue reading