One from the archives: an interview conducted in person with Jodorowsky in Burbank back in summer 2003. Jodo’s then-forthcoming book on the Tarot has since been published, and is now available in English as The Way of Tarot: The Spiritual Teacher in the Cards (Destiny/Inner Traditions). Click on the cover above for purchase info at amazon. Here’s a 4.2mb PDF excerpt from the book, courtesy of the publisher. Also: Jodorowsky and Allen Klein reconciled prior to Klein’s death last year, and as a result, all of Jodo’s ABKCO films are now available on dvd.

In the Heart of the Universe

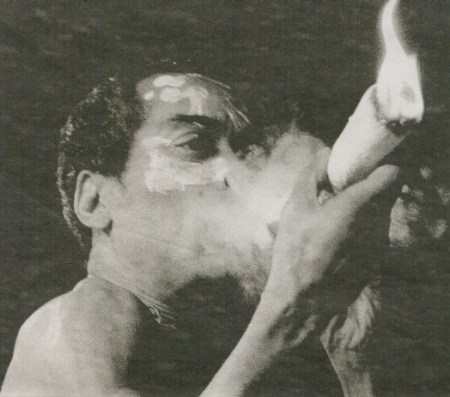

Jay Babcock talks with visionary comics author Alexandro Jodorowsky

Originally published in LAWeekly on January 01, 2004

In 1970, Alexandro Jodorowsky was launched into the counterculture consciousness via an utterly outre film called El Topo, which screened for seven straight months at a theater in New York City. Violent, mystical and more outrageous than Bunuel or Fellini’s surrealist dreamaramas, El Topo was the first midnight movie, a Western that divided critics even as it gained a rabid cult following of turned-on heads including John Lennon, Yoko Ono and Dennis Hopper. Without the benefit of advertising, the film showed seven nights a week to packed audiences. “Within two months,” said the theater’s visionary manager, Ben Barenholtz, who booked the film, “the limos lined up every night. It became a must-see item.”

Allen Klein, infamous manager of the Beatles and Rolling Stones, signed Jodorowsky to a film deal. An El Topo book was published by Lenny Bruce/Miles Davis/Jimi Hendrix/Last Poets producer Alan Douglas—its first half was the film’s nominal screenplay; the second half was a lengthy, startling interview with the auteur.

Born in 1929 and raised in a Chilean seaside town by Jewish-Russian immigrants, Jodorowsky had early ambitions as a poet. Dropping out of university, he formed a puppet company that toured Chile. He left for France in 1953 to find the Surrealists. With Artaud’s The Theater and Its Double as his bible, Jodorowsky worked in film, theater and with mime Marcel Marceau—for whom Jodorowsky wrote various ingenious scenarios. He spent the ’60s bouncing back and forth between France and Mexico — in France, he co-founded the post-Surrealist Panic Movement with Spanish playwright Fernando Arrabal, and in Mexico he drew a weekly comic strip, wrote books, staged plays and finally directed his first real feature-length film, a Dali-esque version of Arrabal’s play Fando y Lis. The Fando y Lis was scandalous and barely screened, but it allowed Jodorowsky to raise the money to make El Topo, the film that would bring him into the English-language world.

By summer 1972, anticipation for Jodorowsky’s next film was high enough for Rolling Stone to send a correspondent to Mexico for a visit to the set of his new film, The Holy Mountain. The resulting article, which was second-billed on the magazine’s cover to a piece on Van Morrison, described scenes, props and conversations that bordered between sensational and plain mad. Participants in the film seemed to be in awe of what they were doing: One P.A. said, “You know, I think this is the most important thing going on in the world today. At the very least, it’s the most far-out.” The finished film may be just that — if you can find it. At some point around the film’s release, Jodorowsky and Klein had a serious falling out that continues to this day, which means The Holy Mountain has never received a legitimate release on videotape or DVD (bootlegs are, of course, available).

In the following years, Jodorowsky attempted to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune to film. The project ultimately failed, but it drew Jodorowsky into contact with French comics artist Moebius, who, along with Swiss artist H.R. Giger, had contributed design and storyboarding work to the film. Jodorowsky began to collaborate with Moebius on comics, and a new career was born.

Indeed, when I sat down with Jodorowsky this past summer for an hourlong conversation, the extent of that career was obvious: He was hard at work on scripts for six different comics projects. Collaborating with a host of the world’s finest talents during the last 25 years, Jodorowsky has found in comics an art form that can accommodate his seemingly boundless imagination. And what comics they are: the Philip K. Dick-gone-cosmic series The Incal, the Homeric space opera The Metabarons, the revenge/ redemption series Son of the Gun, the strange Western Bouncer. With the opening of Humanoids Publishing’s North American branch in 1999, most of Jodorowsky’s comic work is finally available in English.

In conversation, the almost 75-year-old Jodorowsky remains dazzling. Speaking in broken English (which has been slightly cleaned up in the following excerpts from our conversation), his tone is generous, self-deprecating, inquisitive and almost childlike in its sense of wonder. He has made only three films since 1972’s The Holy Mountain — the lost-children’s fable Tusk (1980), the gonzo Grand Guignol Santa Sangre (1989), and the make-work The Rainbow Thief (1990) — and although he has often spoken of an imminent return to the form, one guesses that in the business climate of 2003 this has got to be a long shot. He has, however, recently finished a number of substantial projects: a book-length commentary on the Bible, a lengthy restoration of what he considers to be the original Tarot deck, a collection of short stories and a book of poems. And in February, his decades-in-the-making, 400-page guide to the tarot will be published in Europe.

Q: You are at work on an alarming number of projects for someone of any age. Where is all the energy coming from?

ALEXANDRO JODOROWSKY: Energy is coming because I will die very soon. I am old. I have so many things to do, so every day I get quicker, in order to do them! I don’t want to die without doing everything I wanted to do.

Continue reading →