PUBLISHER’S NOTE: You can download this ‘lecture’ as a convenient PDF for $2.00, payable via PayPal, credit card or debit card. Click here to go to the order form. A link containing the PDF will be emailed to you upon payment.

“FREEMAN HOUSE is a former commercial salmon fisher who has been involved with a community-based watershed restoration effort in northern California for more than twenty-five years. He is a co-founder of the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council. His book, Totem Salmon: Life Lessons from Another Species received the best nonfiction award from the San Francisco Bay Area Book Reviewers Association and the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award for quality of prose. He lives with his family in northern California.”

That’s the bio for Freeman off the Lannan Foundation website. We would add that earlier in his life, Freeman edited Inner Space, a mid-’60s independent press magazine about psychedelics; married Abbie and Anita Hoffman at Central Park on June 10, 1967 (see Village Voice); and was a member of both New York City’s Group Image and the San Francisco Diggers. He is a founding director of the Planet Drum Foundation.

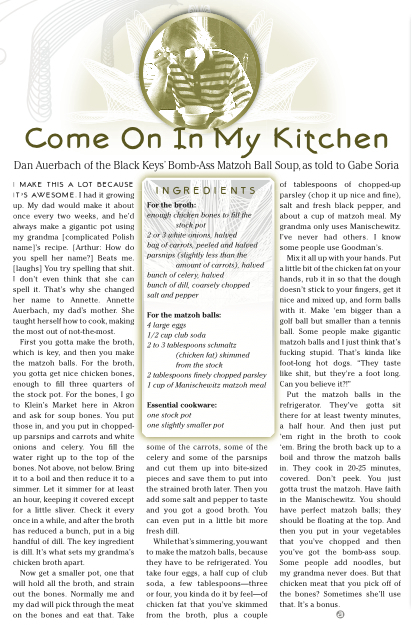

photo by Jim Korpi

RESTORING RELATIONS: The Vernacular Approach to Ecological Restoration

by Freeman House

This piece is based on a keynote talk presented to the 3rd annual meeting of the Society for Ecological Restoration, California chapter, in Nevada City CA, May 1994. It was published in Restoration and Management Notes, Summer 1996.

A couple of years ago, I read a very well-written book that tried to convince me that wherever humans touched nature, nature became un-natural, its beauty and wildness spoiled .The book took notice, correctly I think, that human influence on the landscape had become universal. The writer, Bill McKibben, drew the conclusion that because of this, the end of nature was near. The name of the book is, in fact, The End of Nature (McKibben 1989). Like many environmentalists, McKibben is a passionate man, a man who grieves for injuries to nature. But during the time of writing, he seemed also to be a man who had swallowed most of industry’s argument for the inevitability and (indeed!) naturalness of its destructive behavior in regard to natural systems and human communities. If you accept these arguments—some of which are that economies must grow; that the efficiency of mass production legitimizes its brutalization of human life and and the destruction of natural systems; that mere appetite is the ruling element in human behavior—then McKibben’s conclusions must be correct. If humans are such a sport of nature, if their behavior can only be anti-nature, and if humans are everywhere, then nature must surely be on its way out. It is as if we lived somewhere else altogether than in the ecosystems which provide us with all our needs.

But in fact, humans have always been immersed in ecosystems. And for most of the time we’ve been on the planet, with the exception of the the last few hundred years, humans have behaved as if they were immersed in ecosystems. [1] The paleolithic hunter fails to find his game and returns to counsel with his people. How has their behavior strayed from the path of ample provision? The pre-industrial neolithic planter burns brush, saves seed, collects dung. Alongside deep frugality in the home exist the exuberant public indulgence in great monuments that were observatories of planetary movement, and the devotion of large amounts of time and energy to ceremonial observances of non-human processes and presences in the landscape surrounding. Throughout the industrial age, ecosystem behavior has endured even though its practitioners have been pushed back to the most marginal of land bases.

It is important to understand that behavior which rises out of ecosystems—life lived by immersion—has never been passive but diligently active: symbiotic, reciprocal, deliberately manipulative, and creative. Dennis Martinez, the pre-historian of the restoration movement, has shown us that the indigenous peoples of North America—and by extension elsewhere—have always been an interactive element of the landscape, effecting their own long-term survival with management practices so extensive that ecosystem function was affected (Martinez 1993). This is another view altogether of human relationships to nature. Rather than objectifying nature as a resource base functioning only to provide human wealth and comfort, such cultures express themselves as interactive parts of the natural systems around them. In such cultures, individuals are able to perceive themselves as having no greater (or lesser) a function in ecosystem process than algae, or deer.

Most of us have forgotten how to act this way. Over the recent few hundred years we have been encouraged to forget. There is, in fact, a whole educational industry structured for the purpose of convincing us that our primary identity is as consumers. The question is not how to mourn nature, or how to isolate and protect its tattered fragments, but how to re-engage it and thus rediscover our native wit and adaptive genius. And we will find, I believe, that this rediscovery is possible, but only ever in one place at a time. If we are to re-immerse ourselves in our larger lives, if we are to regain our extended identity, it will be through the portals of individual ecosystems and particular places. Continue reading →